The Role of Orthographic Mapping in Learning to Read

(Note: This post has been updated on April 3, 2022.)

Every word has three forms – its sounds (phonemes), its orthography (spelling), and its meaning. Orthographic mapping is the process that all successful readers use to become fluent readers. Through orthographic mapping, students use the oral language processing part of their brain to map (connect) the sounds of words they already know (the phonemes) to the letters in a word (the spellings). They then permanently store the connected sounds and letters of words (along with their meaning) as instantly recognizable words, described as “sight vocabulary” or “sight words”.

Sight Words

A sight word is any word that a reader instantly recognizes and identifies without conscious effort. Adult competent readers have between 30,000 and 60,000 words that have been orthographically mapped in their sight vocabulary. As soon as one of these words is seen, it is unconsciously and instantly recognizable. This is what enables us to be efficient readers, able to focus on the meaning of what we read instead of on word reading. When words are stored as sight vocabulary words in long-term memory, a reader no longer has to decode words one at a time the way beginning readers do. While some orthographic mapping can begin earlier, most children start applying this skill in second and third grade. As we continue to read into adulthood, we continue to use orthographic mapping to grow our sight word vocabularies.

Because some high-frequency words (e.g., the, and, is, was, for, are) are essential to learning how to read, teachers of kindergarten and grade 1 typically provide explicit instruction to help students automatically read some of these words. Students are taught to read them as whole words at the same time that they are being taught how to decode most other words. However, once students are able to orthographically map, they will start to store high-frequency words as sight words on their own.

What is the mental process of orthographic mapping?

With orthographic mapping of a word, the letters we see with our eyes and the sounds we hear in that word get processed together as a sight word and are stored together in the brain. This is not the same as memorizing just the way a word looks. It is also important to remember that orthographic mapping is a mental process used to store and remember words. It is not a skill, teaching technique, or activity you can do with students (Kilpatrick, 2019). What can be taught are phonemic awareness and phonics skills which enable orthographic mapping.

With orthographic mapping, students connect something new with something they already know. Through listening and speaking, young students already know a word’s pronunciation and meaning which is stored in their long-term memory. Students turn a written word into a sight word by attaching the phonemes in the word’s pronunciation to the letter sequence of the word. The pronunciation of the word has to be broken into its phonemes, which is why having strong phonemic awareness skills is important. The word’s letter sequence can become familiar (i.e., become a sight word) because the student can attach it to the already known pronunciation.

Kilpatrick (2019) provides examples similar to the following:

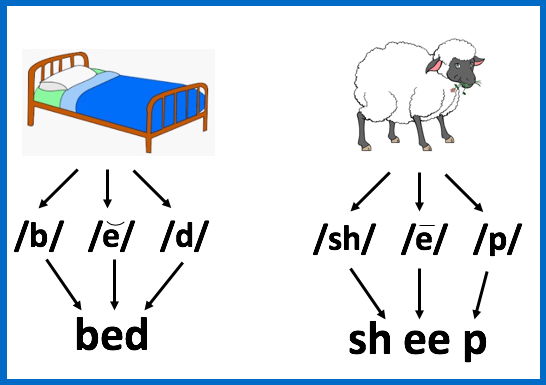

- If a student knows the spoken word /bed/, its pronunciation is stored in long-term memory – he knows what it means and what it sounds like. If he has good phonemic awareness skills, he can pull the word apart into its individual sounds (phonemes) /b/ /e/ /d/. Those sounds become the anchoring points for the word’s printed sequence. The student can then attach each phoneme to its corresponding letter (spelling). The student is using the power of what he knows (the pronunciation) and attaching it like “superglue” to the printed word bed. This example has all single sound-letter correspondences.

- If a student knows the spoken word /sheep/, its pronunciation is stored in long-term memory – he knows what it means and what it sounds like. Using phonemic awareness skills, he can pull the word apart into its individual sounds /sh/ /e/ /p/. The student then attaches each phoneme to its corresponding spelling. In this example, some of the sounds are represented by more than one letter.

In typically developing readers from grade 2 on who have orthographic mapping skills, they only need to see and read printed words one to four times before they become permanently stored as sight words for future instant recall (Reitsma, 1983 as cited in Kilpatrick, 2015). When a word becomes a sight word, as soon as it is seen its sound and meaning are immediately available. Having a significant amount of stored sight words is what enables fluency – quick and accurate reading where the reader is free to focus on making meaning from text.

How does orthographic mapping develop?

Three intersecting skills must be in place to enable orthographic mapping (Ehri, 2014; Kilpatrick, 2015):

- Highly proficient phonological and phonemic awareness

- Automatic letter-sound correspondence knowledge

- The ability to accurately and quickly decode a word by identifying its sounds letter by letter, and blending those sounds to read the word

Here’s how Ehri (2014) explains the skills that need to be in place before orthographic mapping can take place:

“To form connections and retain words in memory, readers need some requisite abilities. They must possess phonemic awareness, particularly segmentation and blending. They must know the major grapheme-phoneme correspondences (letter-sound knowledge) of the writing system. Then they need to be able to read unfamiliar words on their own by applying a decoding strategy.” Doing so “activates orthographic mapping to retain the words’ spellings, pronunciations, and meanings in memory.” (p. 7)

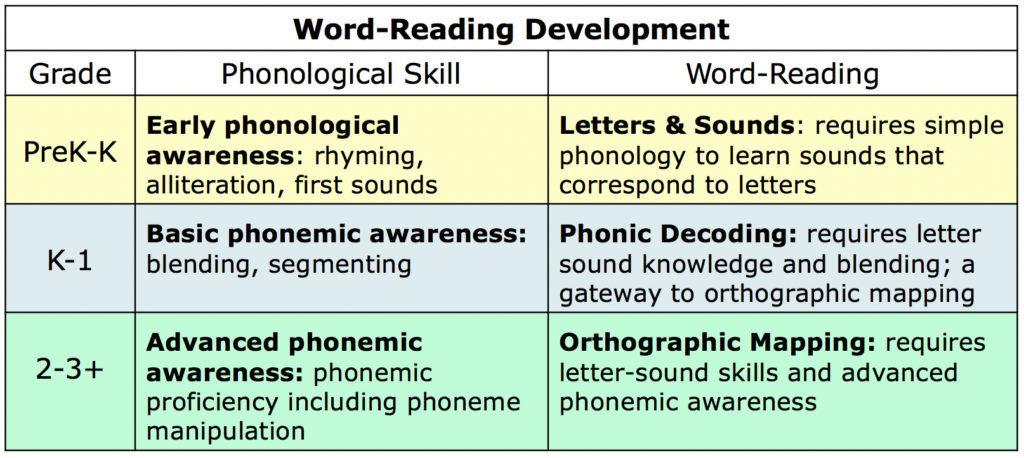

Kilpatrick (2015) describes three phases of word-reading development for children in the primary grades that are aligned with corresponding phonological skill development. As noted above in Ehri’s quote, the ability to segment and blend phonemes is needed to support decoding and eventually orthographic mapping. Kilpatrick has proposed that advanced phonemic awareness activities focused on practice with phoneme manipulation might be helpful for students who are not able to orthographically map words; however, at this time there is not sufficient research to indicate that instruction focused on advanced phonemic awareness improves orthographic mapping.

Beginning readers in kindergarten and grade 1 are developing their knowledge of letter-sound correspondences and basic phonemic awareness skills, and are beginning to learn phonic decoding. Before a student can orthographically map a word, the word first has to be identified. Young students identify the pronunciation of a word by using their letter-sound knowledge to determine each sound in the word, and then using their phonemic blending skills to blend those sounds to decode (sound out) the word.

Once these skills are proficient, typically by grade 3, orthographic mapping usually develops for the majority of students simply by interacting with letters and words. However, many students with word-reading difficulties do not develop orthographic mapping. They therefore have greater difficulty developing the sight word vocabulary needed for fluent reading and will likely stay disfluent and hesitant readers unless they receive intervention that builds proficiency in phonemic awareness (in particular segmenting and blending) and phonics and decoding skills (Kilpatrick, 2015; Parker, 2019). It is difficult for them to get beyond having to decode most words when they read.

Implications for Teaching: Explicit Phonemic Awareness and Phonics Instruction Leads to Orthographic Mapping

Phonemic awareness and phonics instruction help students use the alphabetic principle to learn relationships between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language. As noted in the word-reading development chart above, developing early phonological awareness, including phonemic awareness of initial sounds, should be a focus of PreK and kindergarten instruction to develop basic letter-sound correspondence knowledge. As students move through kindergarten and grade one, a focus on blending and segmenting of phonemes in written words develops phonic decoding skills which must be in place for orthographic mapping. Some kindergarten and grade 1 students may be able to start completing simple phoneme manipulation tasks, such as deleting or substituting initial sounds in words.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCE: After this post first appeared, Joan Sedita presented a webinar titled “The Role of Orthographic Mapping in Learning to Read.” It is now a free, archived webinar at the Keys to Literacy website. Click here to access.

References

- Ehri, L. C. (1998). Grapheme-phoneme knowledge is essential to learning to read words in English. In J. L. Metsala & L. C. Ehri (Eds.), Word recognition in beginning literacy (p. 3–40). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Ehri, L.C. (2014) Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning. Scientific Studies of Reading 18(1).

- Kilpatrick, D.A. (2015). Assessing, preventing, and overcoming reading difficulties. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Kilpatrick, D.A. (2019). Assessing, preventing, and overcoming reading difficulties. Online course. Colorado Department of Education. Retrieved from: https://sitesed.cde.state.co.us/course/view.php?id=132#section-1

- Mather, N., & Jaffe, L. (2021). Orthographic knowledge is essential for reading and spelling. The Reading League Journal, September/October, 2021.

- Parker, S. (2019). Sight words, orthographic mapping, and self-teaching. Stephen Parker blog post, April 22, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.parkerphonics.com/post/sight-words-orthographic-mapping-and-self-teaching

- Reitsma, P. (1983). Printed word learning in beginning readers. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 36, 321-339.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Well written and a clear explanation of the importance of phonemic awareness in the early years for all readers. This article points to the importance of identifying those readers who need intentional instruction in advanced phonemic awareness skills.

Is there a curriculum that you recommend?

There are numerous companies that offer programs that combine phonemic awareness with phonics to explicitly teach the alphabetic principle and develop the blending and segmenting skills that are needed for decoding, as well phoneme manipulation. Fundations, Letterland, Lively Letters to name a few. Some core reading program also include fairly good phonemic awareness/phonics lessons. I think the more important thing is the level of knowledge that teachers have about evidence-based practices for teaching these components, and that comes from quality professional development!

I have been teaching reading to kindergarten students for years but have not really know what exactly I have been doing. I have or my students have had a high success rate, but it is/was the ones that did not get it that I did not know what to do about it. Now I have a better understanding where they may be coming from and where they need to go.

Wonderful article. That’s why we began using Heggerty exercises with our kindergarten program.

Brilliant!

Wonderful article. Thanks for clearing a few things up for me. Now, I know I need to by myself a Kilpatrick book too!

You are welcome!

Excellent article, I actually just finished Kilpatrick’s webinar series and I’m now reading Equipped for Success. This article is very clear and easy to understand I’m very tempted to share it with my district. After reading several books about the science of reading and finally coming to this I’m completely chilled by how I was teaching reading and how many people are still uninformed.

Please do share with your district. I wrote this to try and make a very complex concept understandable to classroom educators who might not have a deep knowledge of phonics instruction.

Hi Heather Where! Where can I find Kilpatrick’s webinar series?? I’m interested in them!

Why are there kids who are unable to read despite phonics being taught in a class?

For decades about 20% have left school as functional illiterates; why is this the case?

There are many students who will learn to read regardless of the approach used to teach reading! They are able to intuit how an alphabetic writing system works and learn the phoneme-grapheme associations without direct instruction (the 20% you mention). However, the great majority of students (especially those who have dyslexia, other learning disabilities), need an explicit approach to teaching the foundational skills of phonological awareness and phonics. Students do learn to read some words as a whole units, many before they enter school, including things like their name and words they see in real life such as on a “stop” sign, or restaurants (e.g., “Wendy’s” “MacDonald’s”). And when kindergarten students first enter school there are some very basic high-frequency words (e.g., my, like ) for which teaching how to decode and spell may be needed before they are taught the phonics concepts in these words. There are some sight words (e.g., was, said) that are not “regularly” spelled using common phonics patterns, but even when these words are taught, students benefit from the teacher segmenting the sounds in the word and pointing to each grapheme to show how that phoneme is spelled. See a related blog I wrote about teaching these kinds of words: https://keystoliteracy.com/blog/high-frequency-sight-words/ The point of this blog post about OM is to highlight that proficient readers learn to read many, many words fluently not by memorizing them one at a time, but by applying phonemic awareness and decoding skills to orthographically map these words in a more efficient way.

Outside of Kilpatrick and Ehri this is the best explanation of orthographic mapping I have read. In fact, your article has helped me understand their work more. Thank you. I really appreciate it.

You’re posts are always very helpful.

Thank you!

Hello Joan,

Interesting and very clear article. The teachers I am working with appreciate it!!! Thank you.

Hi! Will orthographic mapping be an effective tool for improving reading proficiency among primary ESL learners? thank you!

The Orthographic Mapping process occurs for all students as they learn to read, including ESL learners. If these learners are beyond grade 3 and are fluent in reading their first language, then the process will be easier.

‘Young students identify the pronunciation of a word by using their letter-sound knowledge to determine each sound in the word, and then using their phonemic blending skills to blend those sounds to decode (sound out) the word.’

I ask the same question as my question earlier. How do kids who are taught the wrong letter sounds able to blend words?

Michel, Let me try to answer the questions you have sent in about orthographic mapping. One question you had was about the line “Students are taught to read them as whole words at the same time that they are being taught how to decode most other words.” What I was talking about here are the handful of high frequency words such as “the” and “was” that do not follow regular phonics patterns, yet need to be taught to kindergarteners because they are so common. Most of the other words these young children will be reading should be words that contain the basic phonics concepts they are being taught (e.g., short vowels in CVC words, digraphs such as sh, th, consonant blends, etc.). Even the high-frequency sight words that do not follow regular phonics concepts should be taught in a way that has students attending to the individual sounds in these words and the letter(s) that represent the, but the teacher also needs to point out that these are words that don’t follow typical spellings. It’s why we say they are taught to read them as sight words…. but they are still being orthographically mapped. Another question you posed was “how do kids who have been taught sounds represented by consonants with extraneous sounds are able to decode a word by identifying its sounds letter by letter and blending those sounds to read the word?” I think you may be asking about phonemes that are spelled with what is sometimes referred to as silent letters — e.g., “mb” spelling for the sound of /m/ in the word “thumb”. The first phonics patterns to teach are the most basic where there is a single letter representing a phoneme. As students move into grade 2, the more complex phonics patters (such as the silent letter example) are taught. In both cases, when we teach students to decode words, we teach them to focus on each sound in a word and the letter or letter combinations that represent them. I hope this response helps explain why the orthographic mapping process works regardless of how a word is spelled — students attend to the sounds (phonemes) not just the spellings!

hello i have a student behind grade level how do i teach this when the schools use WORDS their way.?

There are many reasons why a student might be behind grade level, so your question is broad. You should visit the videos and webinars at the free resources section of the Keys to Literacy website where you will find a number of teaching suggestions related to vocabulary and other components of reading: https://keystoliteracy.com/free-resources/videos/

I work with students who are Deaf or hard of hearing. Their oral language skills are often impacted by their hearing status. I work heavily on developing their oral language skills and use visual cues for segmenting and blending phonemes (tapping on the shoulder for the first sound, elbow for the second, wrist for the third when segmenting and then running my hand smoothly down my arm to blend). Are there any other tips/tricks/ideas you have for working with students who don’t have strong oral language skills?

Since I don’t specialize in the literacy instruction for students with hearing impairments, I can’t offer you some specific suggestions. But in general, being as multi-sensory as possible (as you are doing with the arm touching and visual cues) would be my recommendation!

Very interesting article.

Thank you for this very clear and informative article. You have really cleared up some questions I had about how to help the young students I work with (kindergarten through 4th grade). I do have one question: I am surprised to read that the ability to orthographic map words doesn’t really develop until 2nd grade, if I’m understanding you correctly. Does this mean that it’s developmentally normal for my kindergarten students to see the same CVC words (e.g. “bed”) many times and still have to sound them out each time? I had thought that even at the kindergarten level, students would be beginning to orthographically map words as they are seeing them, blending them, reading, writing them etc. But maybe I’m expecting too much of them, and it’s normal for them to need many repetitions before developing automaticity in the words we’re working on.

Good question about when young ones can OM! The process can begin to take place earlier than grade 2, but it is at grade 2 that it really ramps up!

It can’t be stressed enough as to how important early intervention for students who struggle to remember letter names and sounds.

Orthographic Mapping (according to Kilpatrick, Sedita and others is achieved when “words are stored as sight words in long-term memory so that a reader no longer has to decode words one as a time the way beginning readers do”. I am working with a little 6 year old who seems to have difficulty ‘remembering’ the connection between sound and letter in short vowel words and I am wondering if this is a ‘memory’ issue. If in case it is a ‘memory’ issue can you recommend specific ways to enhance memory skills so that they can be applied in the orthographic mapping of words?

First, from a developmental standpoint, most students begin developing orthographic mapping in grade 2, so if the child is 6 he or she may not have developed enough decoding skills or sufficient, automatic knowledge of letter-sound correspondences to be able to use the OM process to map phonemes to graphemes. As for why this child is having difficulty mastering letter-sound correspondences, rather than he or she having a memory deficit, it is more likely that he or she just needs more explicit, systematic instruction for letter-sound correspondences. It is especially helpful when that instruction provides prompts that help them make that connection, such as pictures that help students associate the letter with the sound. For example, a picture of a snake is used next to the letter s… the student is asked to say the picture and focus on the first sound (i.e., /s/). Then the students say the word (snake) the sound /s/) and the name of the letter (s). Some phonics programs also provide other prompts to help the students develop automaticity, such as a song or a gesture (e.g., rub you tummy when you say the sound /m/ along with the prompt word mouse and the name of the letter m. The Letterland program is an example that provides multiple prompts to help the students remember. If children haven’t mastered that letter-sound knowledge, it will then be difficult to start decoding words.

OK So what are specific steps to be followed and mastered in order to foster the process in the brain that leads to orthographic mapping? Teachers need specifics, not generalities.

Once teachers understand how the OM process works, it becomes clearer why it is so important to provide explicit, systematic instruction for letter-sound knowledge, blending and segmenting phonemes in words to decode, and advanced phonemic awareness (phoneme manipulation). These are the underlying skills that build proficiency in the ability to link knowledge of word meaning, sounds in words, and the spellings of those sounds.

Where can I read or watch more!

There is a 50-minute, archived webinar that explains OM in more depth available at the Keys to Literacy free resources section of this website. Go to https://keystoliteracy.com/free-resources/videos/ and then scroll down through the list of free videos and webinar recordings until you come to the OM webinar!

Very informative and helpful in improving my reading instruction.

Thank you for explaining that phonics instruction aid students use the alphabetic principle to learn relationships between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language. My kid is now starting to read even at a very young age. I want her to develop her reading skills more so I’m planning to buy a jolly phonics book for students.

The break down of the process is very helpful.

Orthographic mapping is a combination of of sounds (ear) and spelling (sight). All efficient readers complete the orthographic mapping process. This process involves both the eyes and ears. A word goes through the orthopedic map which actually becomes a sight words. You only need to read a word 1 to 4 times before it because a sight word.

This validates what my partner teacher and I did with our intervention students. We did Haggerty with our second graders and invited struggling third graders to join us. We didn’t use the term orthographic mapping but we knew that foundation of phonemic awareness – blending and segmenting was important for their advancement as a reader.

I see the difficulty with orthgraphic mapping with some of my students. I know that I have to go back to the beginning with them in terms of my teaching to skills that they should have mastered in kindergarten and 1st grade, I have seen some success and look forward to learning more strategies t0 help them.

How would you suggest orthographically mapping 2 letter blends, such as bl, cl, br, cr, sc, sn, etc.?

I think you may be asking how a teacher might use phoneme-grapheme mapping to show students how the sounds in a word are represented by a letter(s). Blends are considered two separate sounds, so each would have it’s own “box”. With the word “blot” each sound would be mapped separately: /b/ /l/ /o/ /t/. Digraphs on the other hand, such as “th” or “sh” represent one sound.

Great article! How would you explain the difference between orthographic processing and visual processing (as such found in a specific learning disability)?

They are very different things. Orthographic mapping is the process the brain goes through to “save” words to they can be accessed to support fluent reading. I think you may be referring to visual memory deficits that some students with learning difficulties may have. In those cases, the student has a more difficult time remembering visual input for written words.

What are some effective strategies that can be used to assist students with dyslexia in developing orthographic mapping skills?

Explicit instruction of sound-letter correspondences; making sure students identify the phonemes along with the spelling of words.

This is very helpful

Reading this article was a good reminder of the importance of orthographic knowledge when reading. I intend to utilize orthographic mapping in small group instruction to assist students with phonemic awareness.

Very informative and easily understood.

Hello Joan!

Your article was very helpful in breaking down tricky concepts. Based on what you wrote, it seems that orthographic mapping continues to occur well into adulthood. However, I teach middle school students (grades 6-8) who are lacking basic phonemic awareness and phonics skills which has caused their orthographic mapping to also be significantly stunted. What kinds of phonemic awareness/phonics activities would you recommend for much older students? . Almost all phonemic awareness/phonics activities out there are for much younger children and my 13-14 year old students will not engage with it. Additionally, once students hit middle school, state standards pull time and instructional efforts towards more abstract literary concepts that students are expected to master. Do you know of any meaningful activities that can be done daily in short periods of time to support phonemic awareness and phonics acquisition?? I do not want to neglect my readers struggling with basic reading concepts, but am struggling to find ways to integrate those skills into a middle school ELA curriculum.

Thank you for your help!

It is always tough to find time to fill in the gaps for foundational skills for older students who still struggle to decode words! And you are right, much of the material out there for teaching foundational skills is designed for young children. But we owe it to these students to get their reading skills up as high as possible rather then give up on them. First it is important to keep in mind that at the age you are talking about, there is no need to do phonemic awareness practice without letters…. i.e., as you teach students all the letter-sound correspondences and then do blending and segmenting of phonemes in words to decode and spell them, letters should always be used, not just manipulatives (such as bingo chips) for things like Elkonin Boxes. In fact, phoneme-grapheme mapping using letters is best for the older students. Your best bet is to use a research-based intervention program designed to teach basic phonics to older struggling students. And be sure to use it with fidelity and provide sufficient time to do the lessons. If your students are that far behind in their basic reading skills, significant time will be needed to catch them up.

If a grade 4 student can read a book at his grade level. But reads quite slowly.knows all the words. Is this an orthographic mapping problem? If so how can we make him become more fluent. Thank you.

If the student is reading and comprehending a grade-level text, and is able to orally read all the words accurately, then the students is not having difficulty with reading! Some students need to read more slowly, but it the student is comprehending, then there is not problem with orthographic mapping.

This article was very informative about orthographic mapping and how a strong foundation of explicit phonemic awareness and phonics instruction can help students to successfully develop orthographic mapping. Since I teach 3rd grade, I can better understand where students are coming from once they reach 3rd grade.–I can see the different areas for a student that may be in need of intervention by examining the “Word-Reading Development” diagram.

Glad you found it helpful! Some students begin the orthographic mapping process as early as grade 2, and later for others who struggle with beginning reading skills.

As a Pre-K teacher I understand the importance of word-reading development for students in my classroom. This particular skill development is a stepping stone for corresponding phonological skill development. Providing this foundation will allow students the decoding skills to be successful in orthographic mapping.

I appreciate the information in this article. It is truly applicable to the teaching profession.

This was a good refresher about beginning reading skills. As a fifth grade teacher, good to think about those struggling students and what area of deficiency they might need extra support.