Developing Phonemic Awareness Using Letters

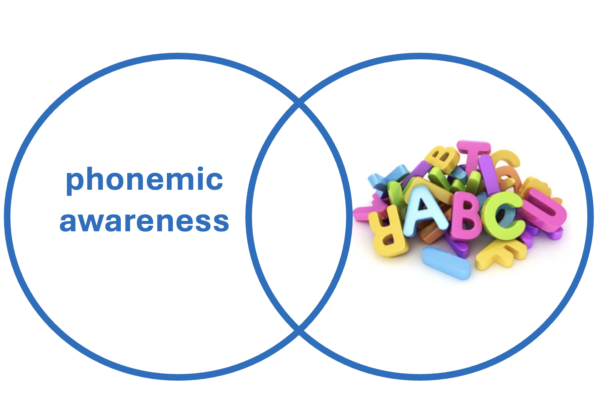

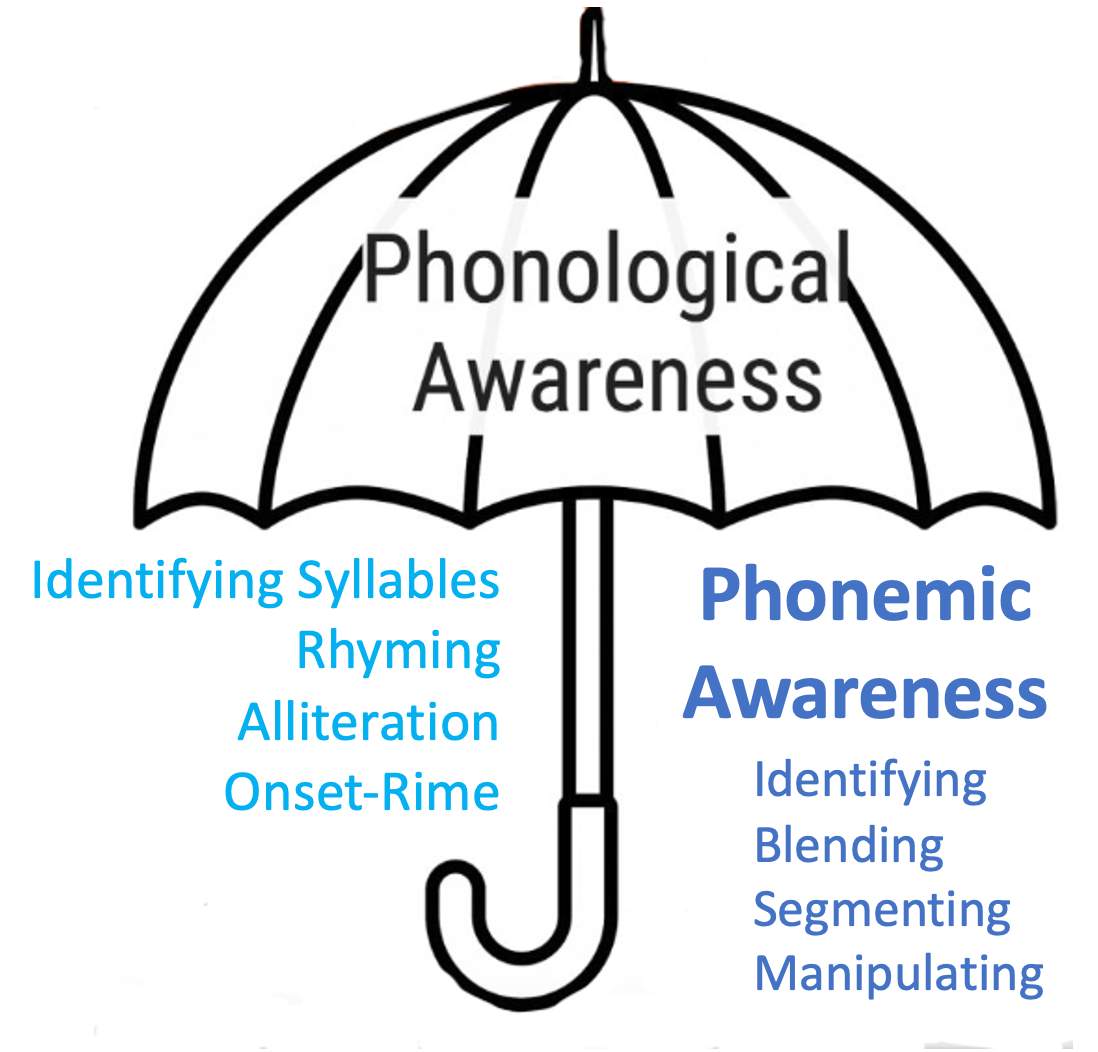

Phonological sensitivity developed using oral language (such as syllable awareness, sensitivity to rhyming, awareness of alliteration, and awareness of onsite-rimes in spoken words) is an important part of emergent literacy skills for young children (ages 4-5) in preK and beginning kindergarten. They are precursors to phonemic awareness, which is the phonological task most related to learning to read and spell words in any alphabetic system (Ehri, 2004). Phonemic awareness is the ability to identify, blend, segment, and manipulate individual sounds (phonemes) in words. This post highlights the importance of developing phonemic awareness using activities that include letters.

Collectively, the skills listed above fall under the broader umbrella of phonological awareness. Adams and colleagues pointed out over 25 year ago the following about phonemic awareness:

Before children can make any sense of the alphabetic principle, they must understand that those sounds that are paired with the letters are one and the same as the sounds of speech… research shows that the very notion that spoken language is made up of sequences of these little sounds does not come naturally or easily to human beings. Fortunately, many of the activities involving rhyme, rhythm, listening, and sounds that have long been enjoyed with preschool-age children are ideally suited for this purpose. Adams et al., 1998

It is important to emphasize that while activities designed to develop phonological sensitivity can be done with young children without seeing letters, once students are taught letter naming and begin learning how sounds and letters correspond (in kindergarten and grade 1), instruction should focus on identifying, blending, and segmenting individual sounds in written words using letters.

The Alphabetic Principle, Phonemic Awareness, and Phonics

The alphabetic principle is the concept that letters and letter patterns represent the sounds of a spoken language. When students understand the alphabetic principle, they have graphophonemic awareness. They must have this understanding in order to learn decoding and spelling skills because written English uses an alphabetic system.

Phonics instruction helps students use the alphabetic principle to learn the relationships between the letters of written language and the sounds of spoken language. Phonics instruction teaches how the 26 individual letters and letter combinations (graphemes) represent the 44 sounds (phonemes) in the English language. Learning that there are predictable relationships between sounds and letters allows students to apply these relationships to both familiar and unfamiliar words and to begin to read with fluency.

Once students are seeing letters in words as they blend, segment, or manipulate spoken phonemes, these tasks should be completed using letters. This approach has not always been widely embraced, as explained by the International Dyslexia Association (2022):

Based on earlier research findings, “over the years an assumption was widely accepted by researchers – and implemented by practitioners – that instruction should follow a sequence from larger to smaller phonological elements. However, research has confirmed that phoneme awareness can be taught to children who lack phonological sensitivity, demonstrating that acquiring phoneme awareness does not require students to first gain syllable segmentation skills. Multiple findings also corroborate that programs are effective when they begin with a focus on phoneme awareness rather than phonological sensitivity, and highly so when instruction then links phonemes with graphemes. This is documented both for beginning readers and for students who have struggled with acquiring reading skills. This research indicates that phonological sensitivity instruction (with larger units such as rhyme, syllables, and onset-rime) is neither a prerequisite nor a causal factor in the development of phonemic awareness.”

A Reciprocal Relationship

Phonemic awareness facilitates the alphabetic principle, and phonemic awareness is enhanced as students learn phonics. Dr. Tim Shanahan made the following points about this reciprocal relationship in his 2020 blog post Letters in Phonemic Awareness Instruction or the Reciprocal Nature of Learning to Read.

“Many educators tout the idea that phonemic awareness is an auditory skill and that it, therefore, must be learned auditorily. …. The reason I say that it makes more sense to teach phonemic awareness with letters than without is because research shows that instructional routines that do that end up with greater success (NICHD, 2000)…. Foundational skills help readers to progress with higher level ones. That means phonemic awareness facilitates decoding and spelling. However, trying to apply phonemic awareness within decoding and spelling refines and extends that ability.”

He goes on to explain the reciprocal nature of reading skill development, where foundational skills support a more higher skill, and a higher skill supports the lower one, citing Perfetti and Beck’s quote, “Phonemic knowledge and learning to read are reciprocal.”

Phonemic Awareness Using Letters: Connections to Research

While oral-only phonemic awareness instruction can positively affect word-level reading and spelling abilities, phonemic awareness instruction using letters is more more effective.

One of the most well-established findings in beginning reading research is the important relationship between phonemic awareness and reading acquisition. The research guide Foundational Skills to Support Reading for Understanding in Kindergarten Through 3rd Grade (Foorman et. al., 2016) recommends teaching students to recognize and manipulate sounds in speech, teaching students letter-sound relations, and using word-building and other activities to link students’ knowledge of letter-sound relationships with phonemic awareness. The report notes:

The National Reading Panel (NRP) report found that teaching students to recognize and manipulate the segments of sound in words (also referred to as phonological awareness) and to link those sounds to letters is necessary to prepare them to read words and comprehend text. Recent evidence reviewed for this guide supports the NRP’s conclusion. To effectively decode (convert from print to speech) and encode (convert from speech to print) words, students must be able to identify the individual sounds, or phonemes, that make up the words they hear in speech. Teachers should begin the instruction described in this recommendation as soon as possible. These activities support students in breaking down the sounds within spoken language and then mapping individual sounds to printed letters. p. 14

A more recent study by Erbeli, Rice, Xu, Bishop and Goodrich (2024) found that phonemic awareness instruction with letters led to bigger returns than activities practiced orally only. The authors of a 2021 article (Clements et al.), based on a review of the research related to phonemic awareness instruction, concluded that while phonemic awareness is an important part of beginning instruction, especially when integrated with print, advanced phonemic awareness focused on phoneme manipulation without using print is not effective. The authors further conclude that time spent with the latter may use up valuable instructional time that could be spent on beginning reading instruction.

Instructional Suggestions

Phonemic awareness tasks range from simple to complex. The easiest task is simply identifying and isolating a phoneme within a spoken word. Blending and segmenting are the tasks most tied to decoding and spelling words. Adding, deleting, and substituting are manipulation tasks, the most challenging. Students who are readily able to manipulate phonemes likely do not have difficulty with phonemic awareness. On the other hand, some students will be able to learn phonics and read even if they have difficulty with phoneme manipulation tasks. For most students, proficiency with blending and segmenting is sufficient for learning to read. Therefore, teachers should not assume that students must become proficient with phoneme manipulation before they can participate in phonics instruction.

Here are some suggestions for blending and segmenting phonemes in words using letters (from the Keys to Beginning Reading teacher training course):

- Blending sounds in a word is critical to learning to read because fluid blending helps students produce recognizable words. Segmenting sounds in a word is critical to learning to spell.

- Once students have established a few letter-sound correspondences (a few consonants and a few short vowels), they can blend them together to read words (decode) and segment to encode (spell) words.

- Students need explicit instruction and practice to the point of automaticity with blending and segmenting the individual sounds of letters in words without stopping between them. The goal is “sounding out” with a fast pronunciation of a word.

- Begin with blending words that have continuant consonant sounds as the first sound (f, l, m, n, s) because they are easier for students to blend.

- Provide guided practice and immediate feedback, following a gradual release I do it, We do it, You do it approach.

- Remember to model correct pronunciation of the individual sounds during blending and segmenting activities.

- Incorporate multisensory strategies such as moving letter tiles while blending.

References

- Adams, M.J., Foorman, B.R., Lundberg, I., & Beeler, T. (1998). Phonemic Awareness in Young Children. Paul H. Brookes.

- Clemens, N., Solari, E., Kearns, D. M., Fien, H., Nelson, N. J., Stelega, M., … Heoft, F. (2021). They Say You Can Do Phonemic Awareness Instruction “In the Dark”, But Should You? A Critical Evaluation of the Trend Toward Advanced Phonemic Awareness Training. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ajxbv

- Ehri, L.C. (2004). Teaching Phonemic Awareness and Phonics: An Explanation of the National Reading Panel Meta-Analysis. In P. McCardle & V Chabra (Eds.). The Voice of Evidence in Reading Research. Paul H. Brookes.

- Erbeli, F., Rice, M., Xu, Y., Bishop, M.E., & Goodrich, J.M. (2024) A Meta-Analysis on the Optimal Cumulative Dosage of Early Phonemic Awareness Instruction, Scientific Studies of Reading, DOI: 10.1080/10888438.2024.2309386

- Foorman, B., Beyler, N., Borradaile, K., Coyne, M., Denton, C. A., Dimino, J., Furgeson, J., Hayes, L., Henke, J., Justice, L., Keating, B., Lewis, W., Sattar, S., Streke, A., Wagner, R., & Wissel, S. (2016). Foundational skills to support reading for understanding in kindergarten through 3rd grade (NCEE 2016-4008). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- International Dyselxia Association. (2022) Building Phoneme Awareness: Know What Matters

- National Reading Panel. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

- Shanahan, T. (2020). Letters in Phonemic Awareness Instruction or the Reciprocal Nature of Learning to Read. (Shanahan on Literacy)

Related, Supplemental Resources

- Webinar: Rethinking Phonological Awareness Instruction: Focusing on What Matters (Dr. Susan Brady, sponsored by edWebinars)

- Podcast: Phonemic Awareness: Unpacking Recent Meta-Analysis Findings with Dr. Florina Erbeli and Dr. Marianne Rice (Teaching Literacy Podcast)

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Wouldn’t teaching phonemic awareness, using letters, simply be phonics?

Good point Tanya! The big idea I wanted to convey in this blog post is that phonemic awareness instruction is best taught and practices as part of phonics instruction using letters as soon as students are introduced to letters. As I noted in the post, phonemic awareness supports phonics and phonics supports phonemic awareness.

I find a very interesting and slightly different point of view of PA development and instruction on Dr. Mark Seidenberg’s blog: https://seidenbergreading.net/2024/08/06/on-the-phonemes-in-phonemic-awareness/. As we are dealing with the SCIENCE of reading, I am not bothered by different points of view as we continue to grow this body of knowledge.

Thanks, Debbie, for connecting to Dr. Seidenberg’s comments about phonemes. He makes an important point that separating phonemes in words while speaking is not natural – when we speak, we tend to “glom” our sounds together and the position of phonemes within a word also creates allophonic variations (multiple pronunciation varients for the same phoneme). And his questioning of teaching 44 sounds in isolation is a point well taken. However, in order to teach students letter-sound correspondences (an important step in understanding the alphabetic principle), beginning reading instruction needs to include some instruction where students focus on how phonemes are represented by graphemes. And in order to blend and segment to decode and spell words, students need to purposely focus on individual sounds in words. This is why in my post I wanted to emphasize that phoneme instruction should be tied to teaching kids how to read, using letter to do so as soon as possible!

My introduction to the Science of Reading began in 2000, when I first learned of the National Reading Panel report. It is exciting to see the names of the researchers that I became so familiar with have continued to study the complexity of learning to read. We know that very young children learn to say whole wards in relationship to things in their environment (mom, dad, cat…). Though we can use the same parts of the brain to segment words, it requires some teaching to break cat into /c/ /a/ /t/. This activity seems to be adjacent to natural speech rather than actually natural. I can see teaching letters and sounds together as soon as students develop understanding of the alphabetic principal. However, I encounter struggling readers every day who cannot decode and encode because they can’t blend phonemes or segment words. I remember teaching reading before we knew about the importance of phonemic awareness and I know that most 3rd graders who struggle to read also struggle with phonemic awareness. I hope we will remember the importance of all the parts of the Reading Rope.

Great reminder for me! I (a sight reader)who was trained by Joan Sedita in the early stages of Language! Program in the 1990’s.