Disciplinary Literacy

As students advance through middle and high school grades, the required level of literacy skills increases significantly to meet the growing demands of reading and writing in different content areas. Students need to be able to understand the language used in school texts that becomes increasingly complex and specialized. This post focuses on what is frequently described as disciplinary literacy – what it is, how it is different from basic reading skills and content literacy (i.e., general reading skills and strategies), and the role that content area teachers can play in helping students develop the literacy skills needed to support content learning. This post is a shorter, adapted version of the content in a recent white paper I wrote titled Disciplinary Literacy: Integrating Literacy Instruction in All Subjects, Grades 6-12.

What is disciplinary literacy?

Disciplinary literacy refers to how an expert in a discipline (i.e., science, history, mathematics, literature, and other subjects) uses specialized knowledge and abilities to read, write, think and communicate. (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008; Shanahan & Shanahan, 2012; Jetton & Shanahan, 2012; Goldman et al., 2016). It encompasses the idea that students need to be taught highly specialized skills that differ from subject to subject, developed as disciplinary habits of mind (Fang, 2012). It presumes that reading and writing are specialized, unique, and vary across the disciplines, and different kinds of texts require different strategies (Schoenbach & Greenleaf, 2009; Shanahan, 2017). Disciplinary literacy is not just learning about a discipline; it is also about reading, writing, speaking, and listening the same way the historian, scientist, mathematician, or literary expert does. Also, the practices inherent in one content area are not generalizable to other content areas, or even within subjects of a single content area (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). Examples include reading and interpreting a calculus word problem, understanding that in science the letter “n” represents the sample size in experimental data, and recognizing that iambic pentameter (a rhythm scheme) used by Shakespeare is specific to literature.

Disciplinary literacy moves beyond content literacy (common reading and writing strategies used across all content areas) and focuses on the unique aspects of specialized texts, forms of writing, and modes of inquiry that experts use in an academic discipline.

A New Focus on Disciplinary Literacy

Experts in the field of literacy began focusing more on the topic of disciplinary literacy beginning in 2008 when Drs. Timothy and Cynthia Shanahan published their seminal 2008 article Teaching Disciplinary Literacy to Adolescents: Rethinking Content-Area Literacy, followed by their 2012 article What Is Disciplinary Literacy and What Does It Matter? In the 2008 piece, they presented data collected from a study that asked how disciplinary experts approached reading and how those approaches might be translated into instruction for high school students. The findings suggested that experts from math, chemistry, and history read their respective texts quite differently. The authors concluded (2008, p. 57):

“This project has helped us rethink the basic content-area literacy curriculum that needs to be taught to preservice teachers in secondary education, and it has revealed the benefits of having a conversation among disciplinary experts, literacy experts, high school teachers, and teacher educators. Instead of trying to convince disciplinary teachers of the value of general reading strategies developed by reading experts, we set out to see if we could formulate new strategies or jury-rig existing ones so that they would more directly and explicitly address the specific and highly specialized disciplinary reading demands of chemistry, history, and mathematics.”

What is content literacy?

Content literacy is skills, strategies, and routines that focus on reading, writing, discussion, word-learning skills, and language that can be used across subjects that are sometimes referred to as generic skills and study skills (CEEDAR Center; Shanahan & Shanahan, 2012; Fagella-Luby, 2012; Shanahan, 2017). Research that has accumulated over decades has supported the use of general reading and writing strategies that are integrated into content classrooms (Brozo et al., 2013; International Literacy Association, 2017; Hwang et al., 2021; Sedita, 2024A).

Shanahan and Shanahan (2012, p. 12) note the following about content literacy:

“It is evident from examining several decades of content area reading/literacy textbooks that the largely agreed-upon purpose of content area reading approaches is to provide students with a collection of generic reading strategies and study skills that will boost learning in all disciplines…. They promote the use of purpose setting and predicting, along with a rich collection of reading processes or strategies (e.g., visualization, summarization, clarification, questioning), and the use of particular study or teaching devices (e.g., Cornell note-taking, three-level guides, advance organizers). A distinguishing feature is that the content area agenda aims not so much to help students read history as an historian might, but rather to read history with a grasp of the information, using a set of generic learning or study tools that may be implemented in any subject. Thus, the focus of content area instruction is less on providing students with an insider’s perspective of a discipline and ways of coping with the unique properties of particular disciplines than on providing students with tools to better remember the information regardless of the nature of the discipline.”

Content Literacy and Disciplinary Literacy Distinctions

The International Literacy Association’s literacy leadership brief Content Area and Disciplinary Literacy (2017) points out that content literacy and disciplinary literacy “are umbrella terms that describe two approaches to literacy instruction embedded within different subject areas or disciplines.” The brief explains that with content literacy, teachers explicitly teach and model reading and writing processes that are common across disciplines and provide opportunities for students to practice them independently or in small groups. Under a disciplinary approach, students use literacy to engage in goals and practices that are unique to each academic discipline. The brief points out the difference between content and disciplinary literacy related to reading and interpreting text (p. 2-4):

- Content Literacy: Students use clarifying questions, read headings and use text structure, summarize, make predictions, and engage in other comprehension or vocabulary strategies and word analysis strategies.

- Disciplinary Literacy: Students read and evaluate texts like somebody in the discipline would, including engaging in critique of these texts and the content in them.

Fagella-Luby and colleagues (2012, p. 69) offer this comparison between content and disciplinary literacy:

“A discipline-specific strategy might teach students historical reasoning to reconcile differences in primary sources; whereas a general strategy might teach students to compare and contrast differences between the two sources. A historical reasoning strategy would be appropriate only with social studies content; whereas the compare-contrast strategy could be generalized to any content.”

Examples of Disciplinary Literacy

What is required for disciplinary literacy in different subjects? View the examples below of discipline-specific requirements, skills and strategies (Schoenback & Greenleaf, 2009; C. Shanahan, 2015; Lent, 2017).

History

Experts in history interpret primary and secondary sources, corroborate sources, and use the past as a prelude to the future. They have the ability to analyze historical documents, attending to bias and perspective, and evaluate the credibility of different sources of information. They also construct evidence-based accounts of probable historical events.

Mathematics

Experts in mathematics decipher mathematical notation in the form of symbols and Greek alphabet letters that represent math concepts. They process abstract ideas, estimate, and generalize. They also understand specialized vocabulary, including words that have different meanings in mathematics than in everyday use (e.g., plane, product, expression, operation, problem).

Science

Experts in science participate in scientific exploration and reasoning. They interpret data, charts, models, illustrations, and lab notes. They also conduct experiments and systematic observations, consider new hypotheses or evidence, and read and write scientific explanations.

English: Literary Works

Experts in literary study closely, read, and examine texts in multiple genres. They recognize literary devices such as hyperbole and personification. They also look for metaphors, conflict, and other features of literature to interpret text. This includes interpreting the symbolism in poems, or how a poem’s form contributes to its theme.

Differences in Language and Text Structure

The text that is used in different content areas can vary greatly in terms of the language and vocabulary, sentence structure, and overall text structure. A historical primary document such as a letter from the eighteenth century is structured differently than a passage from a literary work that includes dialogue between characters. An algebra text about solving linear equations will include explanations and formulas, and science text might include language that describes an experiment and the results. An important part of teaching disciplinary literacy is making students aware of what is unique about a piece of content-area text and modeling how an expert in that discipline would go about reading that text.

Research Supporting Disciplinary Literacy Instruction

What guidance does research provide about teaching disciplinary literacy? There is not a significant research base that shows a disciplinary literacy approach to be highly effective, or studies determining the most effective way to teach disciplinary literacy strategies. In 2012, Goldman pointed out that research related to disciplinary literacy was just emerging at that time and most of the studies were descriptive rather than experimental, yet nevertheless instructive.

In their 2012 article, Drs. Timothy and Cynthia Shanahan noted:

“At this stage, the body of research evidence is not yet sufficient for demonstrating the effectiveness of disciplinary literacy instruction at improving either literacy achievement or subject matter success. Only a few studies testing the efficacy of such methods have been undertaken so far and with mixed results.” (p. 14)

They did go on to say, however, that the approach is promising, and suggested students would make greater progress in reading the texts of history, science, mathematics, and literature if instruction provided more explicit guidance that helped them to understand the specialized ways that literacy works in those disciplines.

Later, in a 2017 blog post, Dr. Timothy Shanahan noted, “Since disciplinary literacy is a relatively new thing for schools, there is a flood of questions about it. And, because the research is lagging classroom demand, there is only a trickle of research-based answers to provide.” In a later 2024 interview for an article in Education Week, Dr. Shanahan noted, “I’d say we we’re at a fairly early stage in disciplinary literacy when it comes to, do you have a lot of studies showing that if you teach this kids achieve more? And I can say we have some. Twenty years ago, I couldn’t say that. Now I can say we have some and we still need more.”

Even with the current limitations in research on disciplinary literacy, this does not mean there is no merit to supporting disciplinary literacy. A compelling case can be made that integrating a disciplinary literacy approach along with content literacy instruction enhances students’ understanding of content and helps them connect literacy skills to real world applications. Educators would benefit from additional research to determine with more certainty what and how content teachers can effectively integrate disciplinary literacy into their classrooms.

Levels of Literacy: Basic, Content, Disciplinary

In 2008, Drs. Timothy and Cynthia Shanahan proposed a model of literacy progression in three levels, in the form of a pyramid, with Basic Literacy skills at the bottom (skills mastered by most students during primary grades such as decoding skills, print recognition, and recognition of high-frequency words). Skills at the Intermediate Literacy level are in the middle (including generic comprehension strategies, decoding multisyllabic words easily, learning academic vocabulary, recognizing more complex forms of text structure, critical responses to text, and gradually more specialized generic reading routines). Disciplinary Literacy is at the top of the pyramid and represents more sophisticated but less generalizable skills and routines specialized to history, science, mathematics, literature, or other subject matter. These high-level disciplinary skills and abilities are not easy to learn since they are applied to difficult texts and are rarely taught.

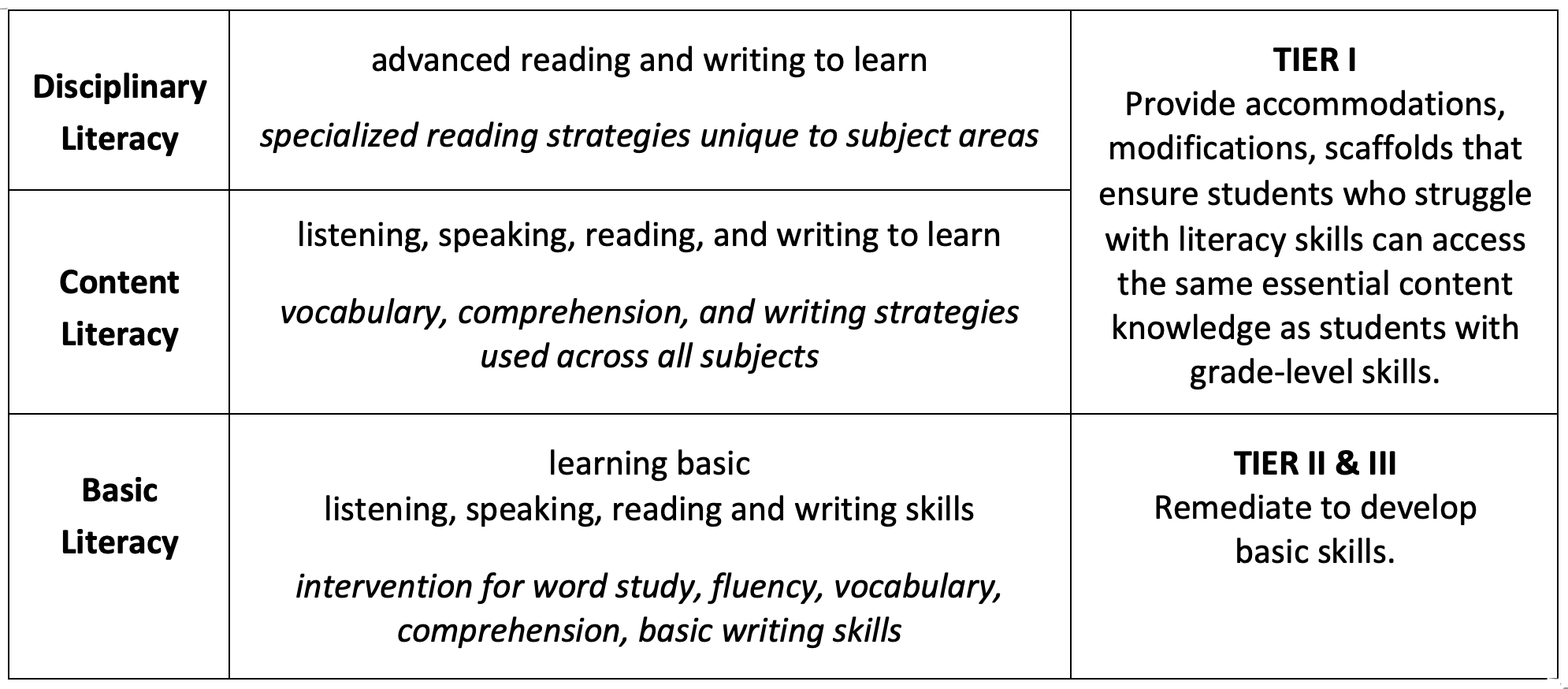

In 2021, I developed a similar model for identifying the levels of literacy that support a Multi-Tiered System of Support framework where adolescent students receive core (Tier I), supplemental (Tier II), and intervention (Tier III) instruction based on the individual needs of students, shown below. The model suggests students in middle and high school grades who have difficulty with reading and writing require Tiers II or III support to develop missing basic, foundational reading and writing skills. This remedial instruction is typically provided outside the content classroom. Content literacy (general literacy skills and strategies that support reading and writing to learn in all subjects) and disciplinary literacy (specialized reading and writing strategies unique to subject areas) are integrated into content instruction as Tier I instruction.

Combining Content and Disciplinary Literacy Instruction in Middle and High School Grades

Most literacy experts suggest that it is best for content teachers to combine content literacy and disciplinary literacy; they are not mutually exclusive approaches. Content teachers play an important role in teaching students how general content literacy skills and strategies are used with the specific content and texts within their discipline. This is where content literacy and disciplinary literacy intersect. Students can practice common generic literacy strategies as they are introduced to discipline-specific frameworks and practices. This is especially the case in middle school grades where many students are still learning how to automatically decode and determine the meaning of multisyllabic words derived from Latin and Greek and increasing their overall fluency skills.

Shanahan (2017) explains that general comprehension skills and study strategies are helpful teaching tools that can enhance student learning from text. He notes that content area reading aims to build general literacy skills, while disciplinary literacy tries to get students to grasp the ways literacy is used to create, disseminate, and critique information in the various disciplines.

Disciplinary literacy practices in some ways re-frame general content literacy strategies for more advanced and specific purposes. Burke and Kennedy (2024, p. 642) make this point:

“Disciplinary literacy provides a helpful way of thinking about how we can integrate our literacy instruction in a manner that serves our literacy aims while remaining true to the ways of thinking and inquiring that a scientist or artist might adopt.”

The guide Reading in the Disciplines (Lee and Spratley, 2010, p. 16) suggests a combination of generic reading and discipline specific reading strategies, shown below.

Generic Reading Strategies

- Monitor comprehension

- Pre-read

- Set goals

- Think about what one already knows

- Ask questions

- Make predictions

- Test predictions against the text

- Re-read

- Summarize

Discipline Specific Reading Strategies

- Build prior knowledge

- Build specialized vocabulary

- Learn to deconstruct complex sentences

- Use knowledge of text structures and genres to predict main and subordinate ideas

- Map graphic (and mathematical) representations against explanations in the text

- Pose discipline relevant questions

- Compare claims and propositions across texts

- Use norms for reasoning within the discipline (what counts as evidence) to evaluate claims

Consider the Needs of Struggling Adolescents

Some advocates of disciplinary literacy view content literacy as something significantly different from disciplinary literacy, and that content teachers should focus only on the latter. Given the deep research base supporting the use of general, content strategies for reading and writing across disciplines, a focus on just disciplinary instruction hinders discussion about how to blend both approaches to effectively teach students with varying degrees of literacy proficiency in content classrooms. This is especially the case for large numbers of adolescent students in today’s schools who have not developed basic literacy skills, most of whom spend the majority of their time in regular classrooms (Fagella-Luby et al., 2012; Brozo et al., 2013) and for some English learners who have not developed sophisticated vocabulary and language skills.

Fagella-Luby and colleagues (2012, p. 76) examined the research base related to discipline-specific strategies and struggling adolescent learners and found the following:

“Of more than 150 articles examined on reading and writing strategy instruction involving struggling adolescent learners, only 12 involved any methods that could be coded as offering discipline-specific strategy instruction. These results support a conclusion that reasoning for a disciplinary framework precedes the necessary evidence base. Moreover, as only 1 of the 12 studies involved content other than reading and writing related to literature, research on outcomes for struggling learners with discipline-specific strategies in core subjects (i.e., science, mathematics, and social studies) is desperately wanting.”

They suggest that content teachers should bear some responsibility for teaching general content strategies, and make the following points:

“Although the disciplinary literacy framework is appealing, regrettably it fails to consider the academic diversity in today’s schools in which a majority of students have yet to master the necessary prerequisite skills for discipline-specific instruction.” (p. 70)

“Although the rationality of developing discipline-specific strategies to improve depth of content area knowledge is clear, replacing general strategy instruction wholly with discipline-specific strategies in high schools at this time is not practical, grounded in a literature base, nor likely to meet the realistic needs of a majority of students. … it is unlikely that adolescents who struggle, who constitute a majority of students, will be able to master disciplinary literacy skills without the necessary prerequisite literacy building blocks that are embodied in general strategy instruction.” (p. 81)

Reading Motivation and Engagement

There is strong evidence that students’ motivation and interest in reading school-related texts declines after they move from elementary to middle school, and this is particularly true for students who have difficulty with reading. Students with low motivation and interest in reading do not read as much as students with stronger motivation. This lack of reading affects the maintenance of fluency, the growth of vocabulary, and effective reading strategies needed to learn from text. This in turn limits their ability to learn in all content areas. (Torgesen et al., 2007; Kamil et al., 2008)

Adolescent struggling readers often lack the motivation to read in school because they face increasingly difficult reading material and classroom environments that tend to deemphasize the importance of fostering motivation to read (Guthrie & Davis, 2003; Murray et al., 2010). They may engage with reading as a passive process without giving effortful attention to activating prior knowledge or using reading strategies. They also often have low comprehension of text and may not be interested in exploring content topics through reading. This is in comparison to their peers who are more motivated, proficient readers who interact with text in strategic ways and are more interested about topics in content texts. (Murray et al., 2010; Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000)

Another challenge facing secondary students related to motivation is that during the school day they are expected to develop disciplinary literacy skills for multiple subjects. Every time the bell rings they enter a new content classroom. Students may have varying interests in different subjects, and some may find certain subjects less engaging or more challenging.

For students who are not proficient readers and lack motivation to read, an emphasis on disciplinary literacy does not adequately meet their needs. These students need explicit instruction on content literacy strategies, and in some cases, basic reading skills before they will be motivated to embrace the challenges of reading like an expert in multiple disciplines.

Overall Instructional Suggestions

Beginning in the middle grades, teachers should strive to adapt general reading practices into more discipline-specific variations. However, they do not have to wait until content literacy skills are fully developed to begin introducing students to disciplinary literacy practices. For example, they can teach students how to review experimental data and write a lab report in science, how to determine the point of view of the author of a primary historical document, or how to determine the theme of a poem even if students have not mastered general content strategies such as note taking and summarizing. As students move into high school grades and encounter more sophisticated disciplinary texts, they need more support to learn discipline-specific strategies (Schoenbach and Greenleaf, 2009).

Here are a few instructional suggestions from the longer white paper about disciplinary literacy:

- Students in upper grades need opportunities to access high-quality, disciplinary texts, not just textbooks which tend to report content information, but not from a disciplinary perspective. This includes being able to see information expressed in different forms (e.g., prose, tables, charts, etc.) often within the same text, especially for science. (Shanahan, 2017)

- Shift responsibility for thinking and making sense of texts to students themselves through guided supports in both small and whole group work. (Lee & Spratley, 2010)

- Use explicit instruction and a gradual release of responsibility model to teach content and disciplinary literacy skills that includes teacher modeling and use of think-aloud.

- Explicitly teach before, during, and after vocabulary and comprehension strategies.

- Help students analyze text and teach close reading skills. This includes reading a challenging text several times, each time focusing on a different aspect of the text: essential vocabulary, difficult phrasing and sentences, the author’s point of view, and the central and main ideas. (Sedita, 2020)

- Incorporate high-quality discussion about text that focuses on the meaning and interpretation of texts in various content areas. This includes teaching students how to use accountable talk and talk moves (O’Connor, 2012; Michaels et al., 2013) during peer discussions.

- Preview vocabulary and provide background knowledge prior to reading.

- Follow well-established, evidence-based adolescent literacy practices. For reading, this includes providing explicit vocabulary and comprehension instruction, providing opportunities for extended discussion of text, increasing students motivation and engagement in literacy learning, and making available intensive and individualized interventions for struggling readers provided by trained specialists (Kamil et al, 2008). For writing, this includes explicitly teaching writing strategies, integrating writing and reading and having students write about text, and teaching the writing process and skills that go into creating text (text structure, paragraph and sentence construction, spelling). (Graham & Hebert, 2010; Graham et al., 2017)

- Create opportunities for teacher collaboration between subject-area teachers and literacy specialists.

Conclusion

All students deserve high quality instruction that prepares them as proficient readers and writers across disciplines to prepare them to be college and career ready. Content teachers play an important role in helping students see the relevance in their lives of disciplinary learning, and teaching them the skills and strategies for reading, writing, and discussion across disciplines.

Educators need to first make sure students who enter middle and high school grades have basic, foundational literacy skills such as decoding and spelling, fluency, basic comprehension skills including inferencing, an understanding of text structure, knowledge of basic academic vocabulary, and basic sentence and paragraph writing skills. If students do not have these skills, they should be provided Tier II supplemental or Tier III intervention instruction.

Tier I, core instruction for grade-appropriate reading, writing, and discussion skills needs to be integrated in all subjects. This should include a combination of general, content literacy skills and strategies, including comprehension strategies (predicting, note taking, summarizing, question answering and generation, etc.); continuous academic vocabulary growth and strategies for determining the meaning of unfamiliar words; recognition of more complex forms of text structure for both reading and writing; writing critical responses to text; and applying the stages of the writing process. Students should be taught to apply these content literacy strategies to gradually more specialized content reading and writing tasks.

Students also must learn to become skilled in disciplinary literacy, i.e., developmentally appropriate forms of reading, writing, and discussing in history, science, mathematics, literature study, and other academic subjects. Dr. Cynthia Shanahan notes (2015) that students are much more likely to increase their ability to read in different disciplines if they know something about the literacy strategies and practices particularly suited to that discipline. This includes learning how texts function within a discipline and understanding the inquiry frames and purposes that readers bring to texts and other artifacts of the discipline (Goldman, 2012). It also includes advanced writing skills needed to complete specific writing tasks unique to each discipline.

Because there is minimal coursework provided in college at the pre-service level and insufficient professional development devoted to secondary literacy instruction, literacy educators and content educators need to find opportunities to collaborate and develop the pedagogical knowledge that enables content teachers to integrate content learning and literacy instruction within each discipline.

To learn more, read the white paper Disciplinary Literacy: Integrating Literacy Instruction in All Subjects, Grades 6-12.

NOTE: This post was updated on December 21, 2024 to include additional information.

References

Brozo, W.G., Moorman, G., Meyer, C., & Stewart, T. (2013). Content area reading and disciplinary literacy: A case for the radical center. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 56 (5).

Burke, P. & Kennedy, E. (2024). Why do you think that? Exploring disciplinary literacy in elementary science, history, and visual arts. The Reading Teacher, 77(5).

CEEDAR Center. Course Enhancement Module on Disciplinary Literacy. Anchor Presentation Speaker Notes. University of Florida. https://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/cems/disciplinary-literacy/#:~:text=Disciplinary%20literacy%20refers%20to%20the,Shanahan%20%26%20Shanahan%2C%202012

Faggella-Luby, M.N., Graner, P.S., Deshler, D.D., Drew, S. V. (2012). Building a house on sand: Why disciplinary literacy is not sufficient to replace general strategies for adolescent learners who struggle. Top Language Disorders 32(1). Pp. 69-84.

Fang, Z. (2012). Language correlates of disciplinary literacy. Topics in Language Disorders, 32(1), pp.19-34. DOI: 10.1097/tld.0b013e31824501de

Goldman, S.R. (2012). Adolescent literacy: Learning and understanding content. The Future of Children 22(2). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ996190.pdf

Goldman, S., Britt, M., Brown, W., Cribb, G., George, M., Greenleaf, C., Lee, C., Shanahan, C., & Project READI. (2016). Disciplinary literacies and learning for understanding: A conceptual framework for disciplinary literacy. Educational Psychology, 51(2), 219-241.

Graham, S.. and Hebert, M.A. (2010). Writing to read: Evidence for how writing can improve reading. A Carnegie Corporation Time to Act Report. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

Graham, S., Bruch, J., Fitzgerald, J., Friedrich, L., Furgeson, J., Greene, K., Kim, J., Lyskawa, J., Olson, C.B., & Smither Wulsin, C. (2016). Teaching secondary students to write effectively (NCEE 2017-4002). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Guthrie, J. T., & Davis, M. H. (2003). Motivating struggling readers in middle school through an engagement model of classroom practice. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 19, 59-85.

Guthrie, J.T., & Wigfield, A. (2000). Engagement and motivation in reading. In M. Kamil, R. Barr, P. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. III, pp. 403-425). New York, NY: Longman.

Hwang, H., Cabell, S. Q., & Joyner, R. E. (2021). Effects of Integrated Literacy and Content-area Instruction on Vocabulary and Comprehension in the Elementary Years: A Meta-analysis. Scientific Studies of Reading, 26(3), 223–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2021.1954005

International Literacy Association (2017). Content area and disciplinary literacy: Strategies and frameworks (Literacy leadership brief). Newark DE: Author.

Jetton, T. & Shanahan, C. (2012). Adolescent literacy in the academic disciplines: General principles and practical strategies. New York: Guilford Press.

Kamil, M. L., Borman, G. D., Dole, J., Kral, C. C., Salinger, T., and Torgesen, J. (2008). Improving adolescent literacy: Effective classroom and intervention practices: A Practice Guide (NCEE #2008-4027). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Lee, C.D. & Spratley, A. (2010). Reading in the disciplines: The challenges of adolescent literacy. New York, NY: Carnegies Corporation of New York.

Lent, R. (2017). Disciplinary literacy: A shift that makes sense. ASCD Express, February 23, 2017. ASCD.

Michaels, S., O’Connor, M. C., Hall, M. W., & Resnick, L.B. (2013) Accountable talk sourcebook: For classroom conversation that works. Institute for Learning, University of Pittsburgh. ifl.pitt.edu/index.php/download/index/ats

Murray, C.S., Wexler, J., Vaughn, S., Roberts, G., Klingler-Tackett, K., Boardman A.G., Miller, D., Kosanovich, M. (2010). Effective Instruction for Adolescent Struggling Readers: Professional Development Module – Second Edition. Center on Instruction. RMC Research Corporation.

O’Connor, Cathy. (2012). Academically Productive Talk: Discussion within Word Generation. PowerPoint delivered August 15, 2012, Baltimore Summer Institute.

Sawchuk, S. (2024). What is disciplinary literacy? Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/what-is-disciplinary-literacy/2024/10

Schoenback, R., Greenleaf, C. (2009). Fostering adolescents’ engaged academic literacy. In L. Christenbury, R. Bomer, & P. Smagorinsky (Eds.). Handbook of adolescent literacy research. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Sedita, J. (2020). Creating a close reading lesson. Rowley, MA: Keys to Literacy. https://vimeo.com/418594517

Sedita, J. (2021). Adolescent literacy: Components of literacy in an MTSS model. Rowley, MA: Keys to Literacy. https://vimeo.com/554738543

Sedita, J. (2024A). In support of main idea and comprehension strategy instruction. Literacy Lines Blog, Keys to Literacy. https://keystoliteracy.com/blog/in-support-of-main-idea-and-comprehension-strategy-instruction/

Shanahan, T. & Shanahan, C. (2008). Rethinking content-area literacy. Harvard Education Review, Cambridge MA: Harvard Education Publishing Group.

Shanahan, T. & Shanahan, C. (2012). What is disciplinary literacy and why does it matter. Topics in Language Disorders, 32 (1) PP 7-18.

Shanahan, T. (2017). Disciplinary literacy: The basics. Shanahan on Literacy. https://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/blog/disciplinary-literacy-the-basics

Shanahan, C. (2015). Disciplinary literacy strategies in content area classes. International Literacy Association. https://www.literacyworldwide.org/get-resources/ila-e-ssentials/8069

Torgesen, J. K., Houston, D. D., Rissman, L. M., Decker, S. M., Roberts, G., Vaughn, S., Wexler, J. Francis, D. J, Rivera,O., Lesaux, N. (2007). Academic literacy instruction for adolescents: A guidance document from the Center on Instruction. Portsmouth, NH: RMC Research Corporation, Center on Instruction.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Leave a Reply