How the Brain Learns to Read

Reading is a relatively new cultural development. While there were some people who could read dating back to the invention of writing during the 4th millennium BC, it was not until after the Industrial Revolution in the 1800’s that large numbers of the population in many countries learned to read. The human brain did not evolve to be able to read the way it did for spoken language. In order to read, the brain has to learn to re-purpose brain functions that were developed over thousands of years for other, more basic needs. Dehaene (2009) describes it this way:

“The brain circuitry inherited from our primate evolution is co-opted to the task of recognizing printed words – the brain’s existing neural networks are “recycled” for reading. Because of something called brain plasticity, during brain development a range of brain circuits can adapt for new uses. When we learn a new skill such as reading, we recycle some of our old brain circuits.”

What parts of the brain are involved in reading?

There is no specific place in the brain that we use to read. Reading involves multiple processes that tap into different regions of the brain. Advances in neuroscience since the 1980’s have enabled scientists to unravel the principles underlying the brain’s reading circuits. Brain imaging using Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (FMRI) enables researchers to create images that reveal information about brain anatomy and activity while reading. It reveals the parts of the brain that activate when we read.

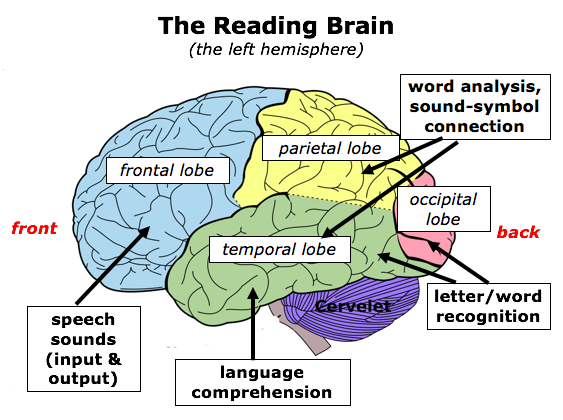

People who become experienced readers use and integrate several regions of their brain, primarily in the left hemisphere including (Cunningham & Rose; Eden; Hudson et al., 2016):

- The parietal-temporal region (towards the back) which does the job of breaking a written word into its sounds (i.e., word analysis, sounding out words).

- The occipital-temporal region (at the back) where the brain stores the appearance and meaning of words (i.e., letter-word recognition, automaticity, and language comprehension). This is critical for automatic, fluent reading so that a reader can quickly identify words without having to sound each one out.

- The frontal region (at the front) which allows a person to speak (i.e., processing speech sounds as we listen and speak).

It is important to remember that while different regions can be identified in terms of playing certain roles in the reading process, multiple parts of the brain during reading are in constant collaboration. Seidenberg (2018) notes that some scientists hold the view that “each major type of information during reading is supported by a network of brain structures rather than localized to a single area and that each brain area is responsive to and participates in the processing of multiple types of information.” (p. 204)

The Brain Changes as We Learn to Read

Every child’s brain has to change the way it functions as the child learns to read. For most students, instruction and practice during the primary grades is sufficient to “train” the regions in the brain to learn to read. Brain imaging research has revealed anatomical and functional changes in typically developing readers as they learn to read (Turkeltaub et al., 2003 as cited in Eden). Cunningham and Rose note that activation patterns in areas of the brain will be different depending on a student’s reading ability.

“For example, beginning readers show more activity in the parietal-temporal (word analysis) region while more experienced readers become increasingly active in the occipital-temporal (word recognition) region. Rich language experiences early in life contribute to making the brain more receptive to the acquisition of reading skills (skills such as phonemic awareness, decoding and word recognition).”

What does brain imaging reveal about struggling readers?

Cunningham and Rose point out that the brain scans of struggling readers show that the patterns of activity are notably different (more scattered than those of strong readers). The pathways for language and cognition are not as efficient and established, so the work of reading is harder for the child even though he or she is trying just as hard.

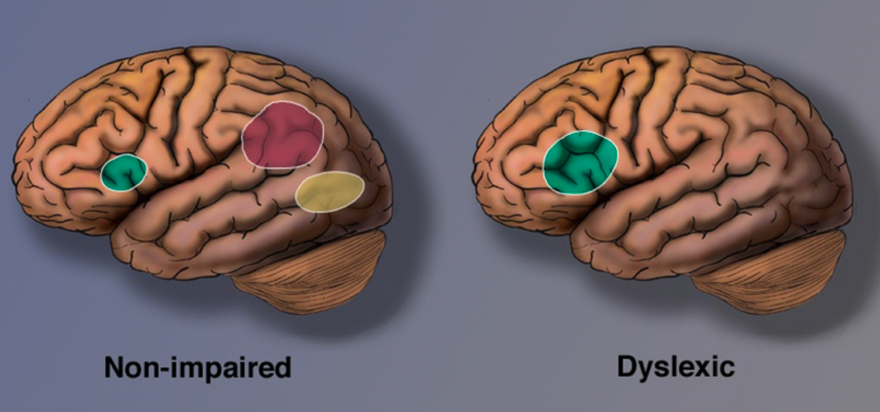

For children with dyslexia, their brains often do not develop in a way that makes them efficient readers. Brain imaging studies have found that the reading process works differently in the brains of dyslexics because there is a neurological cause of dyslexia. Dyslexic readers show under-activation in areas where they are weaker and over-activation in other areas in order to compensate. Instead of using the parts of the brain in the left hemisphere (which is designed to process language), dyslexics who struggle to read use different parts of the right hemisphere which is not efficient (Hudson, High, Otaiba, 2007; Eden, 2016).

Shaywitz et al. (2002) found that children who were good decoders had more activation in the areas important for reading in the left hemisphere and less in the right hemisphere than children with dyslexia. Furthermore, many people with dyslexia often show greater activation in the lower frontal areas of the brain, possibly because their frontal regions may compensate for problems in the regions in the back of the brain (Shaywitz, 2003). The visual above illustrates how the dyslexic brain is activated more in the frontal region, while the non-dyslexic brain is activated in several parts of the left hemisphere.

Can we rewire the brain through instruction?

The good news for people with dyslexia is that their brains will “rewire” themselves if reading instruction is provided that explicitly teaches phonological awareness and decoding skills. The brain has plasticity through our lifetime which means our brains are able to change in order to learn new things. Cunningham and Rose suggest that two variables contribute to strengthening neural pathways that allow students to become strong and successful readers:

- Deliberate practice. Students need to hear and read many different kinds of texts as often as possible.

- Intense instruction. In order to prepare the brain for the increasingly complex texts they will encounter in school, most students need intense instruction toward early mastery of core reading skills — like phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and text comprehension.

Brain imaging studies have shown that when dyslexics are taught to read (and given sufficient practice to become automatic with decoding), their brains create new circuits that connect the language processing parts of the brain with the visual processing part – the same as brains of non-dyslexics. Neuroscientist Guinevere Eden (2016) notes that difficulty mapping language to print is at the heart of dyslexia, and if that skill is addressed through intervention, it gives students the key they need to read. She notes that imaging studies have shown a change in the brain after intervention that targets these skills has occurred and reading is improved. This is not only true for young students, but also for adult dyslexic non-readers. Brain plasticity allows the brain to learn and change even as we get older. The big difference is that the older the student, the more intense the instruction and practice needs to be. The sooner that intervention can be provided, the better.

References

Cunningham, A. & Rose, D. This is your brain on reading. Retrieved from https://www.hmhco.com/products/iread/pdfs/EdWeek_OpEd5_brain_on_reading.pdf

Dehaene, S. (2009). Reading in the brain. New York, Penguin Group.

Eden, G.F. Dyslexia and the brain. International Dyslexia Society. Retrieved from https://app.box.com/s/q2cjihwikwncohy3vmv747h04md6eevn

Eden, G.F. (2016). Dyslexia and the brain. YouTube video. Posted by Understood, Oct 14, 2016. Retrieve from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QrF6m1mRsCQ

Hudson,

N., Scheff, J., Tarsha, M., & Cutting, L.E. (2016). Reading comprehension

and executive function: Neurobiological findings. Perspectives on Language

and Literacy, Spring 2016.

Hudson, R.F., High, L. Al Otaiba, S. (2007). Dyslexia and the brain: What does current research tell us? The Reading Teacher, 60(6), 506-515.

Seidenberg, M. (2018). Language at the speed of sight. New

York: Basic Books.

Shaywitz, S. (2003). Overcoming

dyslexia. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Shaywitz, B.A., Shaywitz,

S.E., Pugh, K.R., Mencl, W.E., Fulbright, R.K., Skudlarksi, P., et al. (2002).

Disruption of posterior brain systems for reading in children with

developmental dyslexia. Biological

Psychiatry, 52, 101-110.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Thanks for the info about learning how to read. My son is young, and I want to help him learn how to read. I’ll look for some books that can help him learn how to read.

You might rather want to look for instruction that helps him learn to read. Most teachers are not trained in methods that initiate and reinforce the connections among phonemic & morphemic awareness, decoding, orthography and etymology.

You should read Seidenberg’s book.

Hey Joan,

Long time no see. I hope all is well by you.

I have a 10th grade student with an interest in the brain and will be using this piece as an entry gate to our look see. Thanks for putting it together.

Excellent article, Joan. Thank you.

Wow, this is such a clear synthesis! I’m going to keep to share with any interested parents. Thank you!!!!