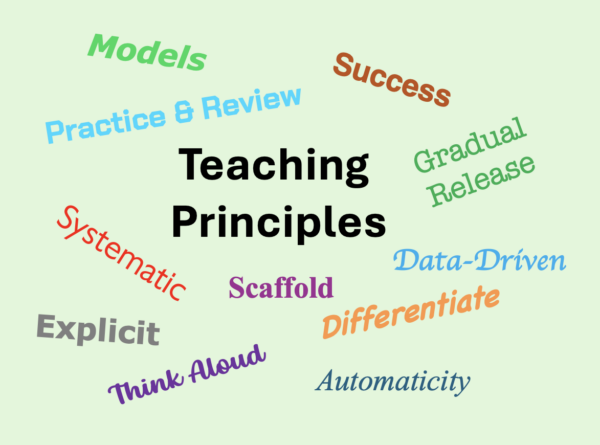

Principles of Effective Literacy Instruction

There are several key teaching principles that help educators address a wide range of learning styles and student needs across all grade levels when teaching reading and writing. These core instructional practices are emphasized in every Keys to Literacy professional development course.

Review the principles below. Which ones do you use regularly? Are there any you would like to incorporate more often?

Explicit, Systematic Instruction

Explicit instruction is a structured teaching approach that guides students through the learning process by clearly explaining a reading or writing skill, modeling its application through think-aloud demonstration, and providing time for guided practice with feedback (Archer & Hughes, 2010). Systematic instruction refers to a planned and logical sequence of teaching, proceeding in small steps while checking for student understanding before moving to the next step. Teachers should follow a scope and sequence that organizes reading and writing skills in a logical order, progressing from basic to more complex concepts. For example, a phonics scope and sequence should begin with basic phonics concepts such as short vowels, digraphs and blends, and then progress to advanced topics like syllables, morphemes (prefixes, suffixes, roots), and multisyllabic word analysis. In writing, explicit instruction in teaching strategies for planning, revising, and editing compositions has been shown to significantly improve the quality of student writing (Graham & Perin, 2007). Hattie (2009, 2023) identified direct and explicit instruction as having a strong, positive impact on student learning outcomes.

Gradual Release of Responsibility (I, We, You)

This model gradually transitions responsibility from teacher to student, leading to independent use of reading or writing skills or strategies (Pearson and Gallagher, 1983). This model should be applied regardless of the skill’s complexity. In the first instructional stage (I do it), the teacher presents a skill through modeling and think-aloud techniques. In the second stage (We do it), students practice the skill together in a whole group or small group, or individually, with the teacher providing guidance and corrective feedback. In the last stage (You do it), students practice the skill independently. The amount of practice and level of support vary for each student before they reach independent use.

Provide Models and Use Think Aloud

Before expecting students to apply a reading or writing skill independently, teachers should demonstrate how to perform the task or skill while explaining each step. Modeling and think-alouds allow students to see and hear what effective skill application looks like. In writing, mentor texts (also called writing models or exemplars) offer students examples of strong writing. These texts help students learn by emulating effective style, text structure, and language. As students grow older and content becomes more complex, it’s important not to assume they no longer need explicit modeling. Clear examples and direct instruction remain essential at all grade levels.

Differentiate Instruction and Provide Scaffolds

Differentiated instruction involves tailoring reading and writing instruction to meet the varied needs of students, rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all approach. A key feature of differentiated instruction is scaffolding, which refers to the temporary assistance provided by a teacher to help students develop skills they initially are unable to grasp independently. As students gain proficiency, the assistance is gradually removed. There are several types of scaffolds: teacher scaffolding, content scaffolding, task scaffolding, and material scaffolding.

Strive for Automaticity Through Practice and Review

When students learn a reading or writing skill at an automatic (mastery) level, they have learned it so thoroughly that they can use it with little or no conscious effort. For example, when decoding and spelling become automatic, students can focus their attention on comprehension during reading and on idea-generation during writing. This is especially important as literacy tasks become more demanding in the upper grades. Consistent guided practice, repetition, and ongoing review of previously taught skills are essential for developing automaticity.

Data-Driven Instruction

Teachers utilize both formal and informal assessment data to inform literacy instructional decisions. It is important to regularly monitor student progress to determine which students are reaching benchmark goals for reading and writing skills and which ones are not. Teachers use data to determine which skills need more explicit instruction and practice, how to effectively group students for instruction, and which students may require supplemental intervention instruction beyond what is provided to all students. The need for real-time formative assessment does not fade as students grow older.

Provide Opportunities for Success

When teachers challenge students beyond their current ability or readiness to learn a new literacy skill, the result can be low self-confidence and reluctance to participate in learning. To introduce a new skill effectively, teachers should begin with simple examples, gradually adding more challenging tasks. It also helps to include practice with previously learned skills along with newer, more challenging tasks, allowing students to experience success and build confidence.

Visit the Professional Development Offerings page at the Keys to Literacy website to learn more about courses that embed these principles into reading and writing instruction.

References:

- Archer, A. L., & Hughes, C. A. (2010). Explicit instruction: Effective and efficient teaching. Guilford Press.

- Graham, S. & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve the writing of adolescents in middle and high schools – A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York: Washington D.C: Alliance for Excellent Education.

- Hattie, J. A. C (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York: Routledge.

- Hattie, J.A.C. (2023). Visible learning: The sequel – a synthesis of over 2,100 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York: Routledge.

- Pearson, P. E., & Gallagher, M. C. (1983). The instruction of reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8, 317-344.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Differentiated instruction means changing reading and writing lessons to fit the needs of each student instead of teaching everyone the same way. Scaffolding is when a teacher gives extra help at first to guide students, and then slowly removes the help as students learn to do it on their own. Scaffolds can include support from the teacher, the way content is presented, the tasks students do, or the materials they use. In 7th grade ELA, I can apply this by giving struggling readers texts with more support, like summaries or guided questions, while challenging advanced readers with more complex texts. For writing, I can provide graphic organizers or sentence starters for students who need help, and gradually remove these supports as they become more confident.