Understanding Dyslexia

October is Dyslexia Awareness Month, so I decided to focus this post on providing information and resources related to teaching reading to students with dyslexia. I first learned about dyslexia at the start of my teaching career in the mid-1970’s when I started teaching at the Landmark School in Massachusetts. At that time, Landmark was a pioneer in the field of learning disabilities and dyslexia, serving over 400 students of all ages each year. The first thing I learned is that even though dyslexia poses challenges to students, it can also be seen a gift. I say this because, while it may be difficult for many dyslexics to learn to read and write, the same neurobiological factors that cause dyslexia also cause many dyslexics to be extraordinarily bright and gifted in many other areas. To learn more about dyslexia, watch the two-part recording of webinars I presented in the spring of 2020 titled “Understanding Dyslexia” (parts 1 & 2). They can be accessed at the Keys to Literacy free videos and webinars page.

What is Dyslexia?

This is the definition adopted by the International Dyslexia Association: “Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.” Lynon, Shaywitz & Shaywitz, 2003

The prevalence of dyslexia is not known for sure. Most experts agree that it affects between 10% to 15% of the population. There are some who say the number is as low as 5% and some who say it is as high as 20%. (Cowan, 2016)

More About Dyslexia

- Dyslexia is a language-based learning disability. Dyslexia is caused by problems with the language processing system, not the vision system.

- Students with dyslexia usually experience difficulties with reading, spelling, writing, and pronouncing words.

- Dyslexia can be mild to severe, ranging from minor spelling challenges to a major impact on the ability to learn to read.

- Many younger students with dyslexia will have difficulty with early speech and language challenges.

- Dyslexia affects individuals throughout their lives; however, its impact can change at different stages in a person’s life.

- In its more severe forms, dyslexia will qualify a student for special education, special accommodations, or extra support services.

- A genetic family history of reading problems is associated with a four-times greater risk of dyslexia.

- Dyslexia often occurs with other learning disabilities such as ADHD, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, and executive functions.

- There are often emotional consequences when students with dyslexia do not get help early. A lack of confidence builds as soon as students start to realize they are not learning to read as easily as their peers.

Misconceptions

- Dyslexia is not a vision problem.

- Eye exercises and vision therapy does not help.

- Colored eyeglasses and colored overlays do not help.

- Changes in size or style of print do not help.

- Dyslexia is NOT seeing words and letters backwards.

- Dyslexia is NOT something that will improve if students just “try harder.”

- Dysleixa is not the result of a lack of intelligence – many people with dyslexia are highly intelligent.

Difficulty with Phonological Processing

Phonological processing is the use of the sounds of one’s language (i.e., phonemes) to process spoken and written language. It includes phonemic awareness and phonological working memory. Most students with dyslexia have inefficient phonological processing skills that affect their ability to learn foundational reading skills. All skills that support typical reading acquisition are impaired by dyslexia. However, because students with dyslexia have a deficit in the phonological component of language, reading difficulty in the early grades tends to center around problems with word reading and decoding skills. Weak phonological awareness skills are found in children with dyslexia as early as kindergarten and often prevail into adulthood. The good news is that interventions that address weakness in phonological awareness are largely successful in bringing about gains in decoding in students with dyslexia. (Eden et al., 2019)

Deficits in phonological processing may affect a student’s ability to learn beginning reading skills in these ways:

Phonemic awareness: awareness and access to the sound structure of language, using speech sounds to code information while reading, speaking and listening

Example: pot cot stop How are these spoken words the same? How are they different?

- If you can recognize the similarities and differences in the sounds (phonemes) in these words, then you can decode and spell words using the sounds in the words.

- If you cannot recognize them, then you must rely on memorizing to read and spell each word which is not an efficient process.

Phonological memory: holding speech-based information phonologically for temporary storage in working or short-term memory

Example:

trying to remember a phone number, someone’s name, or words we pronounce

- If you cannot temporarily remember several sounds (phonemes) or syllables at the same time, it is difficult to decode and spell words.

Dyslexia and “The Reading Brain”

The human brain did not evolve to be able to read the way it did for spoken language. In order to read, the brain has to learn to re-purpose brain functions that were developed over thousands of years for other, more basic needs. There is no single place in the brain that we use to read. Reading involves multiple processes that tap into different regions of the brain. Advances in neuroscience since the 1980’s have enabled scientists to unravel the principles underlying the brain’s reading circuits. Brain imaging using Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (FMRI) enables researchers to create images that reveal information about brain anatomy and activity while reading. It reveals the parts of the brain that activate when we read.

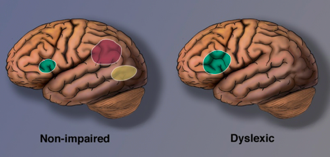

Every child’s brain has to change the way it functions as the child learns to read. For most students, instruction and practice during the primary grades is sufficient to “train” the regions in the brain to learn to read. For children with dyslexia, their brains often do not develop in a way that makes them efficient readers. Brain imaging studies have found that the reading process works differently in the brains of dyslexics due to a neurological cause. Dyslexic readers show under-activation in areas where they are weaker than successful readers, and over-activation in other areas in order to compensate. Instead of using the parts of the brain in the left hemisphere (which is designed to process language), dyslexics who struggle to read use different parts of the right hemisphere which is not efficient (Hudson, High, Otaiba, 2007; Eden, 2016). The graphic below illustrates how the dyslexic brain is activated more in the frontal region, while the non-dyslexic brain is activated in several parts of the left hemisphere.

Can we rewire the brain through instruction?

The good news for people with dyslexia is that their brains will “rewire” themselves if reading instruction is provided that explicitly teaches phonological awareness and decoding skills. The brain has plasticity through our lifetime which means our brains are able to change in order to learn new things. Cunningham and Rose suggest that two variables contribute to strengthening neural pathways that allow students to become strong and successful readers:

- Deliberate practice. Students need to hear and read many different kinds of texts as often as possible.

- Intense instruction. In order to prepare the brain for the increasingly complex texts they will encounter in school, most students need intense instruction toward early mastery of core reading skills like phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and text comprehension.

Brain imaging studies have shown that when dyslexics are taught to read (and given sufficient practice to become automatic with decoding), their brains create new circuits that connect the language processing parts of the brain with the visual processing part – the same as brains of non-dyslexics. Neuroscientist Guinevere Eden (2016) notes that difficulty mapping language to print is at the heart of dyslexia, and if that skill is addressed through intervention, it gives students the key they need to read. She notes that imaging studies have shown a change in the brain after intervention that targets these skills has occurred and reading is improved.

This is not only true for young students, but also for adult dyslexic non-readers. Brain plasticity allows the brain to learn and change even as we get older. The big difference is that the older the student, the more intense the instruction and practice needs to be. The sooner that intervention can be provided, the better. To learn more about how the brain learns to read, here’s a link to a previous blog post.

How Does Dyslexia Affect Components of Reading?

The table below provides some details about how dyslexia affects the learning of various reading skills and suggestions for intervention.

| Phonics & Fluency • Dyslexia makes it difficult to learn how letters represent sounds. • Dyslexia makes it difficult to develop phoneme blending and segmenting skills, making it more difficult to accurately decode and spell words. • The neurobiologically based difficulty with phonological processing skills (including blending, segmenting and manipulation of phonemes) affects the ability to apply the orthographic mapping process to store multiple sight words. This in turn hinders fluent reading. • Dyslexia causes students to read more slowly and use so much energy to decode that they cannot focus on comprehending what they read. Intervention Instruction Provide more explicit, intensive instruction for phonemic awareness, phonics, and fluency skills. Assistive technologies should be provided so that students who are not fluent readers can access grade-level text. This includes recorded audio of text and text-to-speech software (i.e., text readers). Here is a link to a previous blog post with a sample phonics scope and sequence. |

| Vocabulary · Less opportunity to read challenging text leads to less exposure to new vocabulary . · Students with dyslexia need more exposure and practice with a word in order to learn it. · Weak language skills result in more difficulty distinguishing between multiple meanings and the ability to figure out a word from context or its word parts. Intervention Instruction If students can’t read challenging text on their own, provide opportunities for them to be exposed to text with academic language through read aloud or text-to-speech technology. |

| Comprehension · Students with dyslexia read more slowly, placing higher demands on working memory. · Students with dyslexia have weakened ability to determine if they are comprehending or not. · Dyslexia affects the ability to learn, retain, and independently use comprehension strategies. · Over time, dyslexia will affect the motivation to read and make meaning from text. Intervention Instruction If students can’t read challenging text on their own, provide opportunities for them to be exposed to text that contains challenging concepts through read aloud or text-to-speech technology. Provide more explicit, intensive instruction for comprehension strategies, vocabulary, and text structure knowledge. |

References

- Cowen, C. (2016). How widespread is dyslexia? Graphic. International Dyslexia Association. Retrieved from: https://dyslexiaida.org/how-widespread-is-dyslexia/

- Cunningham, A. & Rose, D. This is your brain on reading. Retrieved from https://www.hmhco.com/products/iread/pdfs/EdWeek_OpEd5_brain_on_reading.pdf

- Eden, G.F., Olulade, O.A., Evans, T.M., Krafnic, A.J., & Alkire, D.R. (2019). Developmental dyslexia. Houston Branch of the International Dyslexia Association, 2019 Resource Directory.

- Eden, G.F. (2016). Dyslexia and the brain. YouTube video. Posted by Understood, Oct 14, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QrF6m1mRsCQ

- Hudson, R.F., High, L. Al Otaiba, S. (2007). Dyslexia and the brain: What does current research tell us? The Reading Teacher, 60(6), 506-515.

- Lyon, G.R., Shaywitz, S.e., & Shaywitz, B.A. (2003). Defining dyslexia, cormorbidity, teachers’s’ knowledge of language and reading. Annals of Dyslexia, 53, 1-14.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Do you know how many credit hours the “Understanding Dyslexia” is? Thanks.

The one-day live-virtual or onsite training is 5.5 hours. The asynchronous online course is 6 hours. The facilitated online course is 8 hours.

very interesting and helpful

Dyslexia is a language-based learning disability with a neurological origin. It primarily affects skills related to word recognition, spelling, and decoding, often due to a deficit in phonological processing. Although dyslexia presents challenges in reading, individuals with dyslexia are often highly intelligent. It is not a vision problem, and it does not improve just by trying harder.

Dyslexia can vary from mild to severe, and it may be accompanied by other conditions like ADHD, dysgraphia, and executive function difficulties. Early intervention is crucial, as it helps build confidence and prevents emotional consequences. While dyslexia persists throughout life, explicit reading instruction can help the brain “rewire”

This article highlights how brain plasticity allows students with dyslexia to improve reading through explicit, systematic instruction, deliberate practice, and intense intervention. It reinforces the importance of evidence-based literacy practices.