Motivating & Engaging Adolescents to Read

A significant number of the teacher trainings that Keys to Literacy delivers at schools and districts are focused on teaching reading comprehension, vocabulary, and writing to students in grades 5-12. A common question teachers ask us is, “How can I motivate students to read and stay engaged while they are reading?” This is not surprising given that there is strong evidence that students’ motivation and interest in reading school-related texts declines after they move from elementary to middle school, and this is particularly true for students who have difficulty learning to read (Torgesen et al., 2007; Kamil et al., 2008). This post provides information about this topic and suggests instructional practices associated with improved motivation.

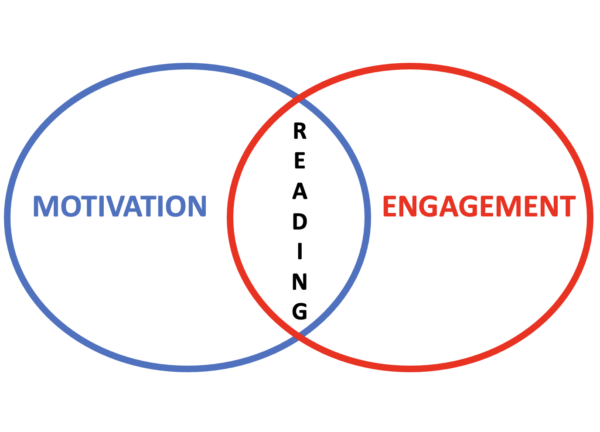

Motivation and Engagement

One of the five recommendations in the Institute of Education Sciences research guide Improving Adolescent Literacy: Effective Classroom and Intervention Practices (Kamil et al., 2008) is for teachers to increase students motivation and engagement in literacy learning. This quote from the guides highlights the difference between motivation to read (i.e., commitment) and engagement in reading (participation).

“Although the words motivation and engagement are often used interchangeably, they are not always synonymous. Whereas motivation refers to the desire, reason, or predisposition to become involved in a task or activity, engagement refers to the degree to which a student processes text deeply through the use of active strategies and thought processes and prior knowledge.” p. 26

Proficient Readers versus Struggling Readers

Murray and colleagues (2020) point out that proficient readers who have a purpose for reading (and sufficient reading comprehension strategies to tackle the text they are reading) have more motivation and are engaged while reading, making reading enjoyable. They use a variety of effortful strategies to make meaning while reading. Motivated readers will also read more, and that reading in turn continues to grow their reading comprehension ability. For example, adolescent students who become engaged in reading a novel of their own choosing or engaged in reading a set of complex instructions for how to set up a new computer, are more motivated and engaged because they are interested in what they are reading and learning from these texts.

On the other hand, adolescent struggling readers often lack the motivation to read in school because they face increasingly difficult reading material and classroom environments that tend to deemphasize the importance of fostering motivation to read (Murray et al., 2010, citing Guthrie & Davis, 2003). Students with low motivation and interst in reading do not read as much as students with stronger motivation (Torgesen et al., 2007). This lack of reading affects the maintenance of fluency and the growth of vocabulary and effective reading strategies needed to learn from text. This in turn limits their ability to learn in all content areas.

Improving Motivation

What can be done to motivate students to read more? First, it should be noted that there is not a large body of research about effective instructional practices to motivate adolescent students to read, including students who have difficulty with reading. However, there is some consensus about four major instructional practices found to have significant effect sizes. These practices were summarized in 2004 by Guthrie and Humenick based on a meta-analysis of research, and updated in 2008 in the Institute of Education Sciences research guide Improving Adolescent Literacy: Effective Classroom and Intervention Practices (Kamil et al.). These are the four instructional suggestions:

- Provide content goals for reading instruction.

- Provide a range of choices in reading activities.

- Afford students interesting texts for reading instruction.

- Increase collaborative reading.

In addition, teachers should pay attention to the level of difficulty of the texts they assign (Mode, 2006; Torgesen et al., 2007). In many content-area classrooms, students are expected to read difficult text that can be overwhelming for students, particularly struggling readers. This can have a significant negative affect on student motivation and willingness to stay engaged in reading such texts. One solution to this is to have texts at different levels of difficulty that address similar content or themes. (Beers, 2003)

Instructional Practices: Suggestions

The detailed suggestions for each of the four practices are compiled and adapted from three sources: Guthrie & Humenick, 2004; Kamil et al., 2008; and Murray et al., 2020.

Provide Content Goals for Reading Instruction

Establish meaningful and engaging content learning goals around the essential ideas of a discipline as well as the specific learning processes students use to access those ideas.

A content goal is a question or purpose for reading. Content goals emphasize the importance of and increase interest in learning from what we read. Teachers can help students find a purpose for reading and foster their curiosity during reading. For example, a student who is reading to find out how panda bears are becoming extinct is more likely to read text carefully and to employ strategies that will help understand the text and answer the question.

Unlike performance goals that emphasize virtues such as completing a task or doing well on a test and may be competitive, content goals are grounded in the attainment of conceptual knowledge.

When teachers set goals to reach a certain standard or acquire particular information, students are more likely to sustain their efforts until they reach those goals. Learning goals can also be set by students, which may make them more apt to be fully engaged in reading to achieve them.

Recommended instructional practices:

- Facilitate the use of relevant background knowledge to increase interest in gaining content mastery.

- Arrange hands-on experiences or other stimulating tasks that lead students to want to find out more by reading.

- Make content goals interesting and relevant by having students read a variety of materials to pursue a theme over a period of time, “publish” a brochure related to a historical event or geographical location, or learn about a topic in order to teach it to someone else.

- Model the behaviors of a curious reader who is rewarded with new knowledge about an interesting topic.

- Involve students in creating content goals and tracking their progress in meeting those goals.

- Give students feedback on their progress in meeting content goals.

Provide a Range of Choices in Reading Activities

Provide a positive learning environment that promotes students’ autonomy in learning.

Allow students some choice of complementary books and types of reading and writing activities. When students choose what they read, what activities they engage in related to reading, and with whom they work, their motivation increases, as does the time they spend reading. They will assume greater ownership and responsibility for their engagement in learning.

Recommended instructional practices:

- Provide opportunities for students to choose which text they read by offering a list of appropriate readings. Students who can select their own reading material use more effective reading strategies and perform better on tests of comprehension.

- Give students control over some aspects of the task such as where to work in the classroom, what type of product to produce (e.g., essay or poster), and which subjects to pursue.

- Allow students to select partners, join groups, or work alone.

Use Interesting Texts

Students enjoy reading texts that they find interesting and choose to continue reading these texts during free time. Further, people remember interesting information more than information they find uninteresting. High-interest text increases motivation to read. It also increases comprehension and achievement. Texts can be chosen by the teacher or students.

Teachers should try to make what students read and write about more relevant to students’ interests, everyday life, or important current events. This includes looking for opportunities to bridge literacy activities outside and inside the classroom.

Guidelines for selecting appropriate and interesting material:

- Choose texts on topics about which students possess background knowledge. Knowing something about a text’s content makes it more interesting. The recommendation is not to avoid introducing new material, but rather to be mindful of the importance of motivation and the effect that unfamiliar content can have on students’ engagement. This underscores the importance of giving students ample background knowledge before asking them to read texts that present new information.

- Texts that are visually pleasing and appear readable are more interesting and motivating. Pay attention to illustrations, layouts, graphics, and text sizes that are appealing and support text comprehension.

- Keep in mind that a text’s relevance and interest is often an individual matter. While some texts are interesting to just about everyone, other texts are interesting only when they support a reader’s content goals.

- To generate interest, provide stimulating tasks related to reading topics prior to reading.

Increase Collaborative Reading

Increase opportunities for students to collaborate during reading. Adolescents are motivated by working together. When students can collaborate socially on reading and literacy tasks, they find the work more motivating and often continue working even after completing the assigned task. Also, collaboration increases the number of opportunities struggling readers have to respond, and when struggling readers are grouped with more capable peers, they are more likely to be successful in the learning task.

Recommended instructional practices:

- Allow students to collaborate by reading together, sharing information, and explaining and presenting their knowledge to others during reading and reading-related tasks.

- Teach collaborative group work skills such as appropriate group work behavior, how to provide feedback to group members, and maintaining individual accountability so that students benefit from working together.

- Use collaboration to foster a sense of belonging to the classroom community.

References:

- Beers, K. (2003). When kids can’t read—what teachers can do: A guide for teachers 6–12. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Guthrie, J. T., & Davis, M. H. (2003). Motivating struggling readers in middle school through an engagement model of classroom practice. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 19, 59-85.

- Guthrie, J.T., & Wigfield, A. (2000). Engagement and motivation in reading. In M. Kamil, R. Barr, P. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. III, pp. 403-425). New York, NY: Longman.

- Guthrie, J. T., & Humenick, N. M. (2004). Motivating students to read: Evidence for classroom practices that increase reading motivation and achievement. In P. McCardle & V. Chhabra (Eds.), The voice of evidence in reading research (pp.213–234). Baltimore: Brookes.

- Kamile, M.L., Boorman, G.D., Dole, J., Kral, C.C., Salinger, T., and Torgesen, J. (2008). Improving adolescent literacy: Effective classroom and intervention practice, a practical guide (NCEE #2008-4027). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

- Moje, E.B., (2006). Motivating texts, motivating contexts, motivating adolescents: An examination of the role of motivation in adolescent literacy practices and development. Perspectives, 32, 10-14.

- Murray, C.S., Wexler, J., Vaughn, S., Roberts, G., Klingler-Tackett, K., Boardman A.G., Miller, D., Kosanovich, M. (2010). Effective Instruction for Adolescent Struggling Readers: Professional Development Module – Second Edition. Center on Instruction. RMC Research Corporation.

- Torgesen, J. K., Houston, D. D., Rissman, L. M., Decker, S. M., Roberts, G., Vaughn, S., Wexler, J. Francis, D. J, Rivera, M. O., Lesaux, N. (2007). Academic literacy instruction for adolescents: A guidance document from the Center on Instruction. Portsmouth, NH: RMC Research Corporation, Center on Instruction.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Yes, practicing writing skills is very important because it allows students to make mistakes and learn from their mistakes without judgement.