The Not So Simple View of Writing

Recently, I’ve been receiving questions about The Writing Rope framework for writing instruction that I developed in 2019, which is also part of the title of a new book that will be published in the summer of 2022. (Click here to read a related blog post). Some of those questions go something like this: “Is there also a Simple View of Writing?” in reference to Gough and Tunmer’s 1986 reading model The Simple View of Reading. So I decided to focus this post on a model that started out as The Simple View of Writing (Berninger et al., 2002) but was then expanded to The Not So Simple View of Writing (Berninger & Winn, 2006).

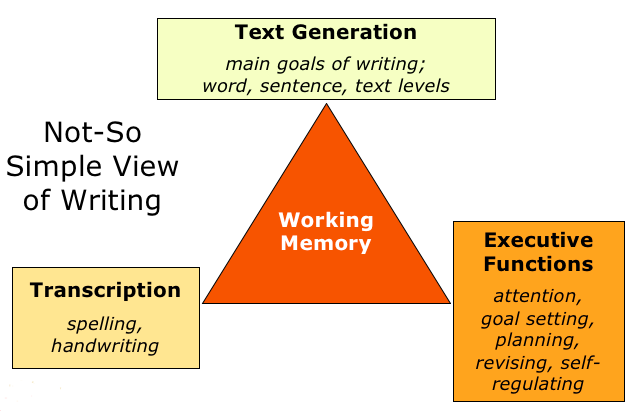

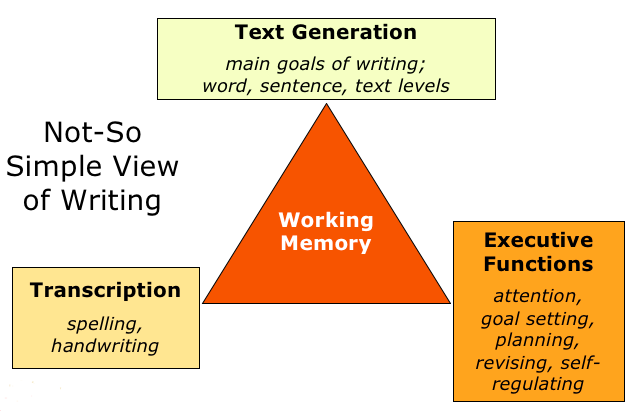

As Kim and Schatschneider explain (2017), the original Simple View of Writing is a theoretical framework focused on writing as the product of two necessary sets of skills: lower-level transcription skills (spelling and handwriting/keyboarding) and text generation (also called ideation, including word, sentence, and text level writing). The Not So Simple View of Writing expanded the framework by adding and emphasizing executive function and self-regulatory processes (e.g., attention, goal setting, reviewing), and working memory (needed during the planning stage of the writing process), and short term memory (needed during the review stage). (Also see Ahmed et al., 2021 explanation).

Visual Representation of The Not So Simple View

This graphic is a visual representation of The Not So Simple View attributed to Berninger. Note the prominent place that working memory holds in relationship to text generation, transcription, and executive functions. Without working memory, writers cannot hold on to what they want to say long enough to be able to decide which words and sentences to write!

Writing is Complex

Proficient writers must integrate multiple skills, strategies and techniques in order to produce a quality piece of writing that reflects what they want to say. The Writing Rope framework organizes these elements into five strands that are woven together to enable skilled writing, listed below. The first four strands are related to the text generation component of The Not So Simple View, with the fifth strand aligning to the transcription component.

- Critical Thinking: Generate ideas, gather information, apply the writing process

- Syntax: Write sophisticated, elaborated sentences

- Text Structure: Apply knowledge of paragraph and longer text structure, incorporate patterns of organization and related transitions

- Writing Craft: Consider the task, audience, and purpose; incorporate writer’s moves

- Transcription: Spell and handwrite or keyboard at an automatic level

But in order to integrate all of these strands, students must have sufficient executive function abilities including attention, the ability to set goals and organize, self-monitoring and regulation, and cognitive flexibility to be able to constantly adjust the application of multiple writing skills (Graham & Harris, 2000; Meltzer, 2010; Cartwright, 2015). Harris, Schmidt, and Graham explain the role of executive functions this way:

“While negotiating the rules and mechanics for writing, the writer must maintain focus on factors such as organization, form and features, purposes and goals, audience needs and perspectives, and evaluation of the communication between author and reader. Self-regulation of the writing process is critical; the writer must be goal oriented, resourceful, and reflective… For skilled authors, writing is a flexible, goal-directed activity, scaffolded by a rich source of cognitive processes and strategies for planning, text production, and revision.” (p. 1)

Simple View or Not So Simple View?

Writing instruction does not receive the same high level of attention in terms of research and discussion about best practices that reading instruction does. The result is that at the present time, it is difficult to find much information about whether educators should refer to Berninger’s model as The Simple View or The Not So Simple View. Some refer to the core elements of Berninger’s theoretical model (transcription, text generation, executive functions, working memory) as just The Simple View, while others are aware of Berninger’s addition of Not So to the title. My guess is that in keeping with the well-known title The Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, 1986), some will find it easier to apply the same title to writing. I prefer to use the longer title that represents Berninger (and colleagues) expanded emphasis on executive function and working memory. Regardless, the important take-away for teachers is to remember that writing is a VERY COMPLEX process, and that we should not forget the important role that executive functions and memory play. It is especially important to keep this in mind when working with students who have difficulty with writing, including those with a specific learning disability.

Click here to learn more about Keys to Content Writing instructional practices for grades 3-12, and click here for Keys to Early Writing. The Keys to Literacy free resources collection also has a number of videos, archived webinars, and templates/printables that support writing instruction.

References:

- Ahmed, Y, Kent, S, Cirino, P.T., & Keller-Margulis, M. (2021). The Not-So-Simple View of Writing in Struggling Readers/Writers. Reading & Writing Quarterly. Link.

- Berninger, V. W., Abbot, R.D., Abbot, S. P., Graham, S., RIchards, T. (2002). Writing and reading: Connections between language by hand and language by eye. Journal of Learning Disabilities 35(1), pp 38-56.

- Berninger, V. W., & Winn, W. D. (2006). Implications of Advancements in Brain Research and Technology for Writing Development, Writing Instruction, and Educational Evolution. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (p. 96–114). The Guilford Press.

- Cartwright, K. B. (2015). Executive skills and reading comprehension. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Gough, P.B., & Tunmer, W.E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7, 6-10.

- Graham, S. & Harris, R. (2000). The role of self-regulation and transcription skills in writing and writing development. Educational Psychologist, 35(1).

- Kim, Y.S. & Schatschneider, C. (2017). Expanding the developmental models of writing: A direct and indirect effects model of developmental writing. Educational Pyschology, 109 (1). pp 35-50. Link.

- Meltzer, L. (2010). Executive function in the classroom. New York: The Guilford Press.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Joan,

You’ve done it again. I really like the infographic and will be using it when I meet (via Zoom) with parents of a child I assessed this month. It makes complex the simple and I appreciate your efforts! Enjoy the Holiday Season (although it seems to me that you work all the time! LOL)

Hello. You mention that working memory is needed during the planning stage of the writing process. Some people might think that the “planning stage” of the writing process is synonymous with “pre-writing,” but can I assume you are also referring to the planning that takes place as the writer is in that act of writing (planning the next sentence, etc/.)

I would also think that working memory is used in the act of “holding the planned sentence in one’s mind long enough to transcribe it.”

It’s a part of writing I never thought about much until I was teaching my Dyslexic son to write a literary essay.

We had homeschooled earlier and were homeschooling again due to covid. We had done EXTENSIVE pre-writing for this essay, and yet, he had taken over an hour to try to get first paragraph done and was now writing through tears. What he had on paper was, frankly, horrible. It hardly resembled the pre-writing we had done (which I had allowed him to dictate to me). My mom heart said ENOUGH, and I told him he could dictate the rest of the paper to me.

The rest of the paper, 3 body paragraphs and a conclusion, were done in the next hour, and done well. Wonderful organization, syntax, etc. It seemed like it was written by a different person but I had transcribed it word for word (only making 2 or 3 minor suggestions about adding details from the text or transition words.).

Afterwards I asked why it was so much easier to dictate it. He said that when he was writing it, before he could get the words down, he would forget what he was going to say.

He was 11 or 12 at the time, finally approaching grade level in reading (though not quite there yet), but far behind in spelling. It was nowhere near automatic. But I think it was taking nearly all his working memory just to handle spelling the words.

Working memory plays a part at multiple stages of the writing process, both before and during. It plays a role before as students are gathering information from sources, and also as they then look at the ideas they have and try to organize them. It also plays a role as you say when actually writing; holding on to multiple ideas while trying to convert them into sentences and paragraphs. In the situation you describe with your son, working memory may be part of what’s causing the difficulty, but the fact that he was able to hold onto all his ideas once he was able to dictate while you wrote means maybe working memory was not the issue. It could be that if his transcriptions skills (spelling, handwriting or keyboarding) are not fluent. By the time students leave grade 3 if these foundational skills are not automatic, many students (especially students with dyslexia) have to put too much cognitive energy into transcription which interferes with their ability to focus on the composing part.

Adolescence is also a vital “window of opportunity” for building core life skills—and for practitioners to provide support.

Literacy is very important for effective writing.

Hi Joan,

You write that text level is a part of text generation, but I don´t quite understand what text level means. Would you like to explain it to me?

Thank you in advance!

I liked the “Working Memory” layout. Great reminders for highe level grade students to reference during their planning steps to create a perfect “paper.”

Keys to literacy is a simple and useful tool for teachers to teach the students how to write.