Connecting the Ropes: Integrating Reading & Writing Instruction

In general, there is a strong case to be made for integrating writing and reading instruction. The Institute of Education Sciences 2017 research guide Teaching Secondary Students to Write Effectively (Graham et al., 2017) notes that reading and writing share cognitive processes and points out the value of writing with a reader in mind and reading with the writer in mind. The research guide Writing to Read (Graham & Hebert, 2020) highlights how writing supports reading and offers the following recommendations:

- Students’ comprehension of content area texts is improved when they write about what they read. Teachers should have students respond to text in writing (including writing personal reactions and analyzing and interpreting text in writing), write summaries, write notes about a text, and answer questions about a text in writing.

- Students’ reading skills are improved by learning the skills and processes that go into creating text. Teaching the process of writing and teaching text structures, paragraph structure, and sentence construction skills improves reading comprehension. Teaching spelling and sentence construction improves reading fluency and decoding skills.

- Students’ reading comprehension is improved by having them increase how often they produce their own text.

However, despite the obvious connections, instruction for reading and writing is often addressed separately when it comes to literacy curricula (one curriculum for reading, one for writing), literacy programs (separate ELA reading and writing programs), and even state literacy standards. For example, the Common Core ELA standards have 10 reading standards that are separate from 10 writing standards. The goal of this post is to highlight the numerous ways the components of reading and writing overlap and make the case for integrating reading and writing instruction within the same lesson whenever possible. This overlap will be explained by pointing out the similarities between two frameworks: Hollis Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001) and the Writing Rope framework that I developed in 2018.

Overviews of the Two Ropes

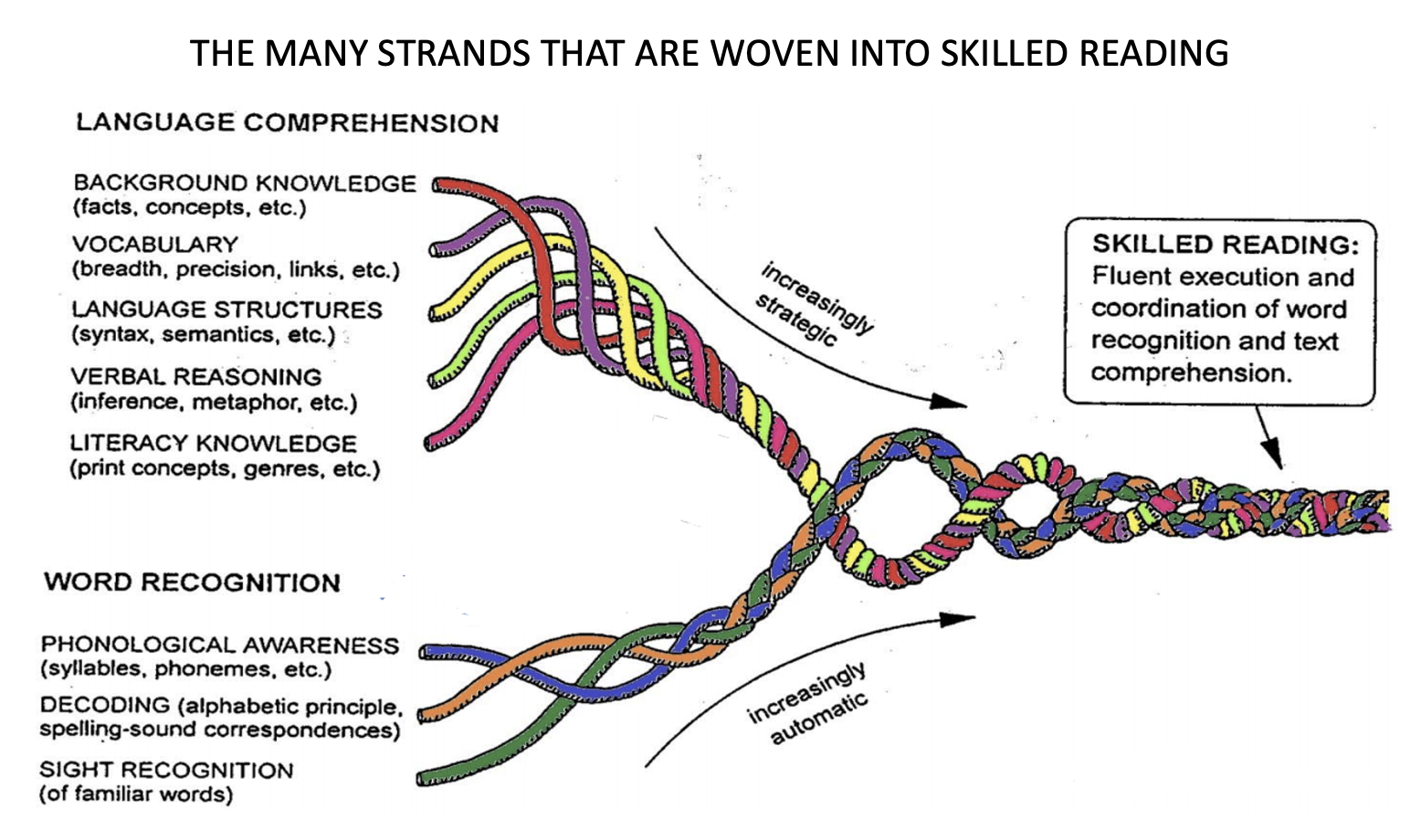

Scarborough’s Reading Rope: The Reading Rope organizes skills and processes into eight components needed for proficient reading, represented as strands in a rope. These components are grouped into two major categories: word recognition and language comprehension. Word recognition is the ability to accurately and fluently decode words in text. Scarborough identifies phonological awareness, phonics, and sight word recognition as skills that contribute to word recognition. Scarborough includes background and vocabulary knowledge, language structures (including syntax), verbal reasoning (including the ability to make inferences), and literacy knowledge (including knowledge of print concepts and genres) under language structure. As students become increasingly more strategic and automatic in the use and integration of these components, they can successfully comprehend while reading. View the graphic of the rope below. For more details, visit the sources listed under resources at the end of this post.

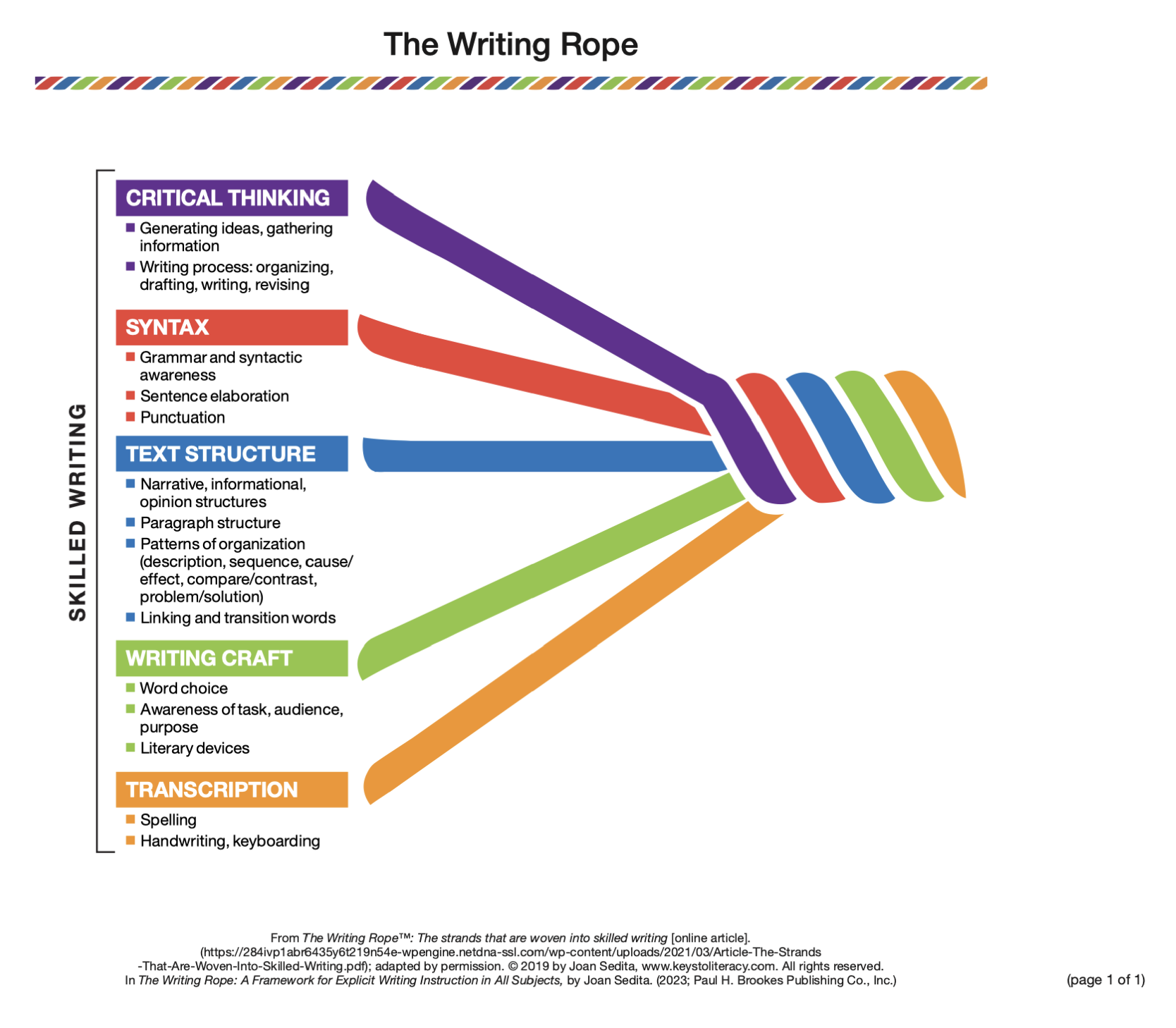

Sedita’s Writing Rope: The Writing Rope organizes the numerous skills, strategies, and techniques that students must learn and integrate to be proficient writers into five components, represented as strands in a rope. The first is Transcription which includes spelling and handwriting/keyboarding. The second is Writing Craft, including word choice, awareness of task, audience and purpose, and use of literary devices. Next is Text Structure which includes structure for the main types of text (narrative, informational, opinion/argument), paragraph structure, patterns of organization (description, sequence, cause/effect, compare/contrast, problem/solution), and linking words that make connections between parts of text and signal patterns of organization. The fourth strand is Syntax, which focuses on sentences (an understanding of grammar and sentence elaboration). The final strand is Critical Thinking which includes knowledge and use of the stages of the writing process, and a number of skills and strategies for generating ideas and gathering information before writing, such as note taking and summarizing. View the graphic of the rope below. For more details, visit the sources listed under resources at the end of this post.

Comparing the Ropes

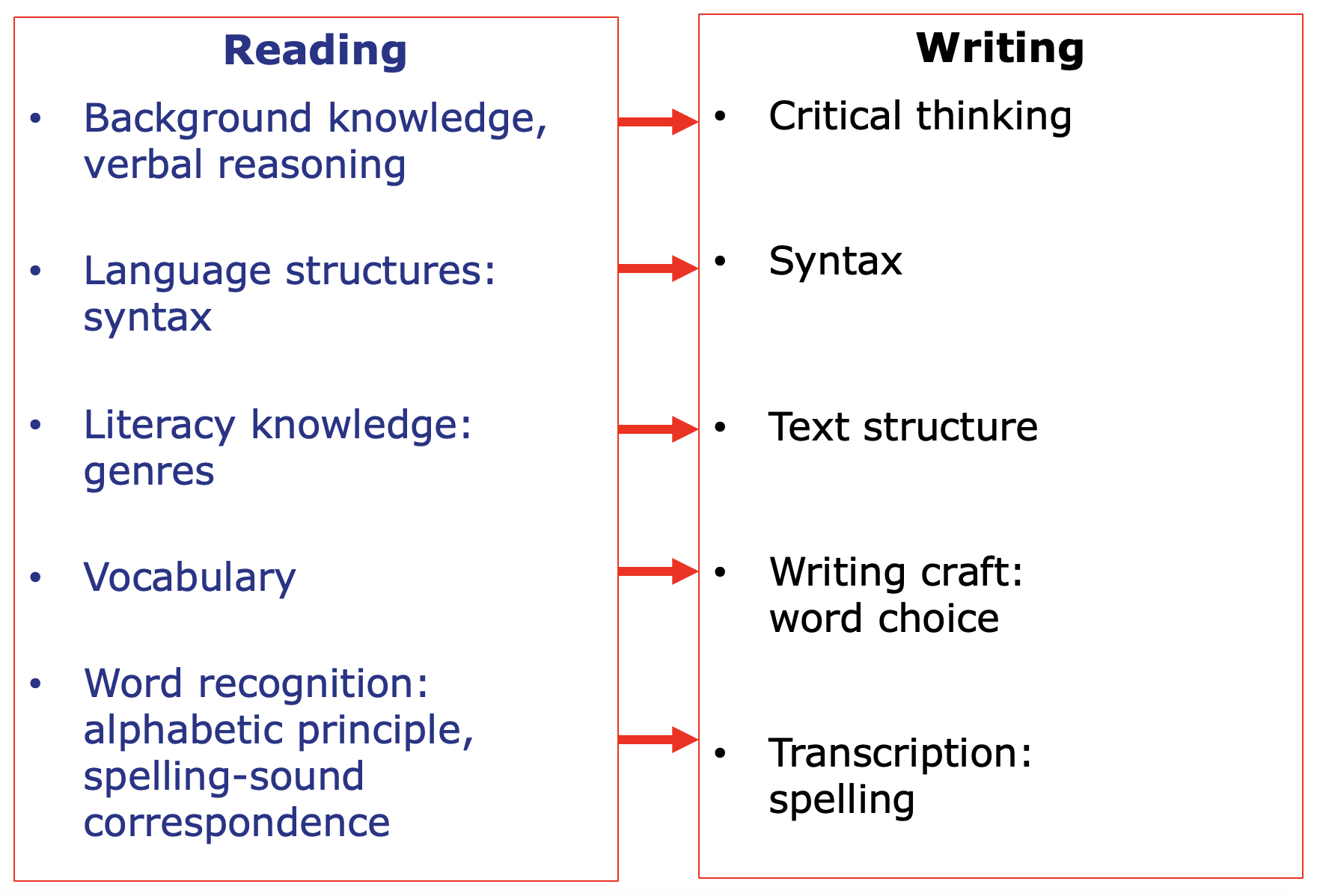

View the two lists above that are connected by arrows indicating how the components in the ropes are aligned. The details below provide an explanation of the overlap between reading and writing.

Word Recognition/Transcription: Foundational skills include knowledge of the alphabetic principle and spelling-sound correspondences (phonics) which are needed to fluently read and spell words. Advanced phonics, also described as advanced word study, includes instruction for syllable types and morphology (meaningful parts in words including prefixes, suffixes and roots), and is important for decoding and spelling longer, multisyllabic words. Lessons focused on phonics and advanced word study should integrate spelling along with decoding practice. For more information about this topic, read my previous blog posts titled Systematic Phonics Scope and Sequence, What is Advanced Word Study? and Spelling Rules and Generalizations.

Vocabulary/Writing Craft-Word Choice: Vocabulary is one of the strands in the Reading Rope, and is represented in the Writing Rope as Word Choice in the Writing Craft strand. One of the oldest findings in reading research is the connection between vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension. If students are not familiar with most of the words in the text, comprehension will be affected. Vocabulary also plays a key role in supporting writing. It is challenging for students with limited vocabularies, especially English learners, to express themselves in writing when they can’t find the words to represent the opinions and information they want to express. Vocabulary instruction throughout the day in all subjects supports both reading and writing. For more information about effective vocabulary instruction, read my previous blog posts titled Building Vocabulary: Semantic Feature Analysis, Vocabulary Instruction for English Learners, Vocabulary Strategy: Use of Context, Vocabulary: Templates for Teaching Words In-Depth, and Previewing Vocabulary Before Reading.

Text Structure: Text structure refers to how a piece of text is built. For reading, it contributes to the complexity of text which affects comprehension, and an understanding of text structure provides clues to making meaning. Knowledge of text structure also improves writing. Text structure is addressed in the Reading Rope under Literacy Knowledge: Genres. One of the five strands in the Writing Rope is devoted to text structure at multiple levels, including the three main types (genres) of text (narrative, informational, and opinion/argument). Students need explicit instruction about overall text structure to help organize their writing by including introductions and conclusions and using the unique structures for developing the body of each type of writing. Instruction about paragraph structure, including that a paragraph is built around a main idea supported by sentences with details, supports reading because it enables students to attend to each new main idea as they read from paragraph to paragraph. It also helps them write more organized writing pieces as they chunk what they have to say into well-organized paragraphs that include topics sentences stating the main idea of each paragraph. Another component of text structure is patterns of organization, including description/explanation, sequence, cause/effect, compare/contrast, and problem solution. Awareness of these patterns while reading supports comprehension, and awareness of these patterns enables students to select the best organizational options for presenting what they want to say in their writing. Transition words and phrases are the final component of text structure identified in the Writing Rope. Transitions link different parts of text and also signal certain patterns of organization. When reading, if students are able to attend to transitions such as first, next, last or however and on the other hand, their comprehension is aided,. Using transitions in their writing makes the content of their writing better organized and accessible to those who read their writing. For more information about effective text structure instruction, read my previous blog posts titled Teaching Text Structure to Support Reading and Writing, The Mighty Paragraph, The Power of Transition Words, and Patterns of Organization.

Syntax: Syntax is the system and arrangement of words, phrases, and clauses that make up a sentence, and when students have syntactic awareness, they understand grammar. Both ropes have strands devoted to syntax. When teachers explicitly teach about sentence structure, students’ reading comprehension of challenging, complex sentences is improved. For writing, instruction about sentences enables students to write varied, elaborated, high-quality sentences. For more information about sentence instruction read my previous blog posts titled Syntactic Awareness: Teaching Sentence Structure Part 1 and Part 2, and Teaching with “W” Questions.

Background Knowledge, Verbal Reasoning/Critical Thinking: Proficiency with skills related to these components is essential for both reading comprehension and writing. They represent the most challenging, high levels of thinking. For reading, students benefit from making connections to their known vocabulary and background knowledge related to the topic of the text they are reading, and in particular, to be able to make inferences from text. Inference is necessary because not all details are stated explicitly in text; readers must draw on text context and their background knowledge to make sense of what they read. This is sometimes called reading between the lines. In order to write about a topic, students benefit from strategies that help them develop and expand their background knowledge about the writing topic. Many writing tasks require critical thinking to identify and gather relevant information before writing, which in turn requires proficiency in strategies that support both comprehension and writing. This includes paraphrasing and summarizing, note taking, and answering/generating questions in writing. For more information about instruction that supports critical thinking, read my previous blog posts titled In Support of Main Idea and Comprehension Strategy Instruction, Scaffolds to Support Summarizing, and Explicit Instruction of Note Taking.

If you would like to learn more about the connection between reading and writing, a 20-minute recorded webinar I delivered in March, 2024 is available titled The Writing Rope: Reading & Writing Connections.

Resources

To learn more about Scarborough’s Reading Rope:

- Article: The Reading Rope: Breaking It All Down (Amplify)

- Slide Deck: The Reading Rope: Key Ideas Behind the Metaphor (The Reading League)

To learn more about Sedita’s Writing Rope:

- Article: The Writing Rope: The Strands That Are Woven Into Skilled Writing (Joan Sedita, Keys to Literacy)

- Recorded Webinar: The Writing Rope: A Framework for Evidence-Based Writing Instruction (Joan Sedita, EdWeb)

References

Graham, S.. and Hebert, M.A. (2010). Writing to read: Evidence for how writing can improve reading. A Carnegie Corporation Time to Act Report. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

Graham, S., Bruch, J., Fitzgerald, J., Friedrich, L., Furgeson, J., Greene, K., Kim, J., Lyskawa, J., Olson, C.B., & Smither Wulsin, C. (2016). Teaching secondary students to write effectively (NCEE 2017-4002). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Scarborough, H. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S.B. Neuman & D.K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (pp. 97-110). New York: Guilford Press.

Sedita, J. (2023). The writing rope: A framework for explicit writing instruction in all subjects. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Excellent insights!

I am a teacher of English as a Second Language. I currently work at the National Institute of Education, at the National Curriculum Division – Humanities Department as a Senior Curriculum Development Analyst for English Language.

This is a superb article. I find your work on the writing rope very interesting and I use these two ropes in PD sessions for teachers around the country.

Would this work? 1. Separate Instruction for Decoding and Language Comprehension

Decoding (Phonemic Awareness and Phonics):

Phonemic Awareness Activities: Focus on sound manipulation, such as blending, segmenting, and phoneme substitution.

Phonics Instruction: Teach letter-sound correspondences, decoding strategies, and word recognition skills. Use decodable texts to practice these skills in context1.

Language Comprehension:

Vocabulary Development: Teach new words explicitly and in context. Use rich and varied texts to expose students to new vocabulary.

Listening Comprehension: Read aloud to students and engage them in discussions about the text to build their understanding and critical thinking skills.

Background Knowledge: Integrate content from various subjects to build students’ knowledge base, which supports comprehension2.

2. Integrating Decoding and Language Comprehension

Bridging Activities:

Decodable Texts with Rich Content: Use texts that are decodable but also contain meaningful content. This helps students practice decoding while also engaging with the text’s meaning3.

Interactive Read-Alouds: During read-aloud sessions, pause to decode challenging words and discuss their meanings. This models the integration of decoding and comprehension.

Guided Reading: In small groups, provide texts that match students’ decoding abilities and guide them through comprehension strategies. Discuss the text to ensure they understand both the words and the overall meaning4.

Explicit Teaching of Integration:

Think-Alouds: Model the thought process of decoding a word and then connecting it to the text’s meaning. For example, “This word is ‘cake.’ I know it has a silent ‘e’ at the end, which makes the ‘a’ say its name. Now, let’s see how ‘cake’ fits into the sentence.”

Context Clues: Teach students to use context clues to infer the meaning of new words they decode. This helps them connect decoding with comprehension5.

Practice and Application:

Reading and Writing Activities: Have students write sentences or short stories using words they have decoded. This reinforces the connection between decoding and meaning.

Comprehension Questions: After reading a decodable text, ask questions that require students to think about the text’s meaning, not just the words6.