Making Inferences to Support Comprehension

I recently read a July, 2024 article by Marianne Rice, Kay Wijekumar, Kacee Lambright, and Ashley Stack titled Promoting Inference Generation: Using Questioning and Strategy Instruction to Support Upper Elementary Students. The piece had some helpful instructional suggestions that build on the content in Module 9: Comprehension of my professional learning course Keys to Beginning Reading. This post shares information and suggestions from that module and integrates some suggestions from their new article.

What is inferencing?

We make inferences every day by reaching conclusions based on clues and reasoning. We figure things out by applying our knowledge and experience to the situation at hand. If we infer that something has happened, we don’t actually see or hear the actual event, but from what we know, it makes sense to think that it has happened. Helping students understand when information is implied in text (not directly stated) will improve their inferencing ability (Reading Rockets).

Inferential thinking is a complex skill that develops over time and with experience. It begins with oral language before students enter school, beginning with everyday conversations, and is supported by real-time context, facial expressions, tone of voice, and opportunities to clarify through collaborative conversation (Snow, 2024).

What is the role of inference-making in reading?

A reader makes inferences by establishing appropriate, meaningful connections between separate pieces of information literally stated in the text and the reader’s background knowledge. It is sometimes called reading between the lines. Making inferences from reading is harder than making inferences from everyday discussions because there are no interpersonal opportunities to support comprehension of an inference. The vocabulary and sentence structure used in text is often more complex, and text may use more idiomatic language (e.g., metaphors the reader may not be familiar with). (Snow, 2024)

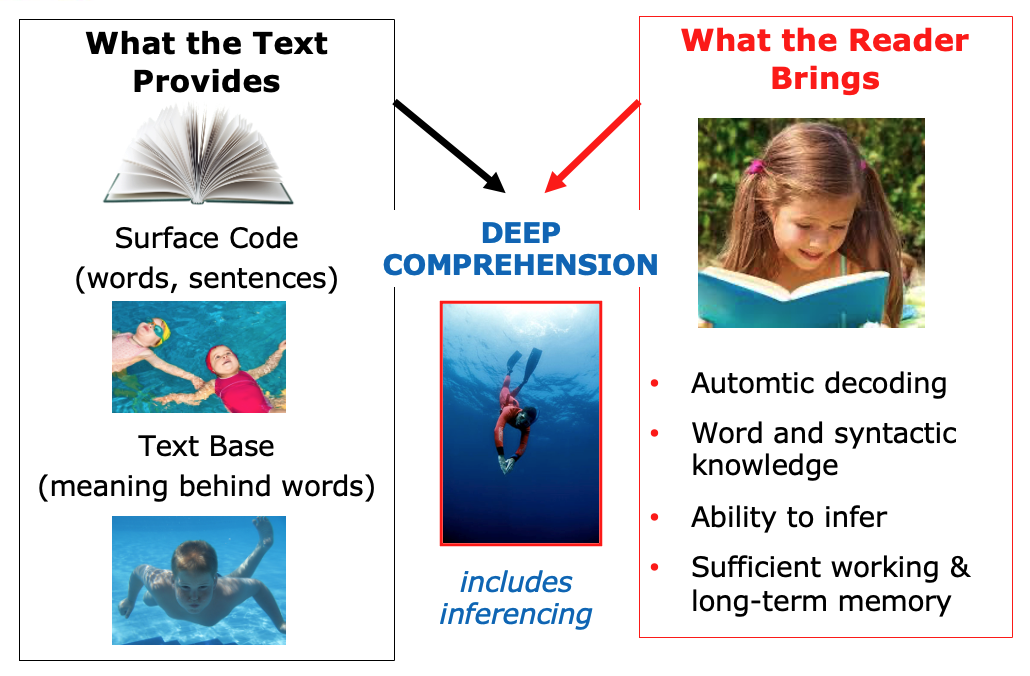

Inference is essential to understanding text passages because authors do not always explicitly state information or explain concepts. Comprehending while reading is sometimes explained as the construction of a mental model that requires readers to integrate information from the text with their own experiences and background knowledge to make full sense of what they read. This is also described as a situation model (Bower & Morrow, 1990; Kintsch, 1998; Zwaan, 2016). The graphic below illustrates the combination of what the text provides and the reader brings to support deep comprehension when reading.

Knowledge-based inferences enable readers to establish causality, draw conclusions, and infer important relationships. These kinds of inferences require students to search their memories and connect knowledge from outside the text with information in the text (The Meadows Center, 2018). Weak comprehenders generate fewer inferences than their more skilled peers and are less likely to engage in integrative processing (Oakhill & Cain, 2016). Background knowledge also enables readers to recognize which of the multiple meanings of a word is appropriate for the text. Catts (2021-2022) shares this example: When reading a passage about baseball, knowing that the word pitcher refers to a person rather than an object is critical for comprehension.

Review the following basic examples and consider how the reader must integrate the context of the text with prior knowledge to be able to comprehend (Oakhill & Cain, 2016). Use the questions to guide your thinking.

Example 1:

Johnny carried a jug of water. He tripped on a step. Mom gave him a mop.

- Why did Johnny’s mother give him a mop?

- What background knowledge is needed?

Example 2:

Bobby was busy with his bucket and spade. The sandcastle was nearly complete. Then a huge wave crashed onto the shore. On seeing that his day’s work had been ruined, Bobby started to cry.

- Why did Bobby start to cry?

- What inference must be made about the sandcastle that is not explicitly stated?

- What background knowledge is needed?

Example 3:

Maria was lying down looking at a reading book. The room was full of steam. Suddenly Maria got soap in her eye. She reached wildly for the towel. Then she heard a splash. Oh no! What would she tell her teacher? She would have to buy a new one. Maria rubbed her eyes and soon she felt better.

- Where was Maria, what was she doing, and what would have to be replaced?

- What were the text clues?

- What background knowledge does the reader need?

Instructional Suggestions

- Preview reading to identify where inference is required.

- Make sure students have the related background knowledge.

- Model and explicitly teach how to look for clues to work out critical pieces of information that are not stated.

- Raise awareness of when inference is needed. Use who, where, why, when questions.

In addition, Rice and colleagues (2024) emphasize the value of inference generation in the classroom by reading a variety of genres (e.g., narrative, expository, poetry) with students to teach and practice inferencing. They also suggest providing an inference question and then helping students identify and link clue words from the passage that would help them answer the question. They use the example of posing a question about an animal, and then teaching students to identify clue words about animals in the text.

The main suggestion in their article is to provide students with lots of opportunities to answer inference questions. Using an explicit approach and following a gradual release of responsibility model (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983), the teacher starts by modeling their own thinking about how to answer the inference question posed. Students are then given an opportunity to answer inference questions with scaffolding as needed. Eventually, students reach independence when they are able to answer questions on their own. Some questions can focus on word meaning (e.g., What does this word/phrase mean in this passage?), questions that focus on integrating pieces of information to gain meaning (e.g., How is this flood similar to other flooding disasters?), and questions related to more elaborate inferences that can require making a background knowledge-based inference (e.g., Based on what you know about _____, why do you think _____?). Teaching students to generate their own questions about text has also been identified as effective in inference instruction studies. Student generated questions can support inference-making, help them get better at answering questions, and improve their metacognition (i.e., their awareness of whether they understand what they read).

For more ideas about teaching questions answering and generation, see three related, previous Literacy Lines posts: Teaching with W Questions, Question Generation: A Key Comprehension Strategy, and Teaching Question Generation.

Use Everyday Examples and Visuals

Introduce inference-making by sharing an everyday example that students can readily relate to. If possible, provide a visual as a scaffold. For example, share the following and ask students what can be inferred:

A small group of adults were standing and sitting in the small shelter on the corner of the city street. Several of them rubbed their hands together and stamped their feet on the frozen sidewalk. One person glanced at the schedule on the wall of the shelter. It was seven o’clock in the morning and the people had briefcases and lunch bags.

Possible Inferences: it was winter, they were waiting for a bus, some of them were taking a bus to work

What were the clues?

- Winter: in the small shelter, rubbed hands together, frozen sidewalk.

- Waiting for bus: shelter on corner of the city street, person glanced at the schedule

- Bus to work: seven o-clock in the morning, had briefcases and lunch bags

Scaffold: Sentence Frames

View the example below of sentence frames that help younger students state their observation and inference.

Explain

When we infer, we combine what we already know with information from a picture or text to understand more than what is already there.

Ask Students

List clues from the picture or text using this sentence frame:

We observe __________.

Then Ask Students Use this sentence frame to state an inference:

We infer __________ because __________.

This post includes content from Module 9: Comprehension in the Keys to Beginning Reading professional learning course.

References:

- Bower, G. H., & Morrow, D. G. (1990). Mental Models in Narrative Comprehension. Science, 247, 44–48.

- Catts, H.W. (2021-2022). Rethinking how to promote reading comprehension. American Educator, Winter 2021-2022.

- Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: A paradigm for cognition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- The Meadows Center for Preventing Risk. (2018). Inference instruction to support reading comprehension for upper-elementary and middle grades students with learning disabilities. Austin, TX: Author.

- Oakhill, J. & Cain, K. (2016). Supporting reading comprehension development: From research to practice. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 42, (2).

- Pearson, P.E. & Gallagher, M.C. (1983). The instruction of reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8, 317-344.

- Reading Rockets. Inference. Website: Reading Rockets – Launching Young Readers. Retrieved from: https://www.readingrockets.org/classroom/classroom-strategies/inferencing

- Nice, M., Wijecumar, K., Lambright, K, & Stack, A. (2024). Promoting inference generation: Using questioning and strategy instruction to support upper elementary students. The Reading Teacher, 78 (2).

- Sedita, J. (2019). Keys to beginning reading. Rowley, MA: Keys to Literacy.

- Snow, P. (2024). Oral language competence is necessary but not sufficient for reading success. PowerPoint Presentation, Plain Talk About Literacy & Learning Conference.

- Zwaan, R.A. Situation models, mental simulations, and abstract concepts in discourse comprehension. Psychon Bull Rev 23, 1028–1034 (2016).

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Very useful, practical ideas.