Teaching Handwriting

A few years ago I developed The Writing Rope as a framework to organize the writing skills that are woven into skilled writing. One of the components is transcription skills, which includes spelling and handwriting. When students develop fluent handwriting skills, they can focus their attention on composing. Difficulty with handwriting can have negative consequences for later writing ability. Teaching handwriting should be an essential part of a writing curriculum.

Stephen Graham (2009-2010) explains it this way:

“Of all the knowledge and skills that are required to write, handwriting is the one that places the earliest constraints on writing development. If children cannot form letters – or cannot form them with reasonable legibility and speed – they cannot translate the language in their minds into written text. Struggling with handwriting can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy in which students avoid writing, come to think of themselves as not being able to write, and fall further and further behind their peers.” (p. 20)

“Young writers typically cope with the multiple demands of handwriting and composing by minimizing the composing process (planning, organizing, etc.). Because so much of their thinking must be devoted to forming legible letters, they turn composing into a knowledge-telling process in which writing is treated as a forward-moving idea-generation activity. A relevant idea is generated and written down, with each new phrase or idea serving as the stimulus for the next one. Mostly absent from this approach to writing are more reflective and demanding thinking activities such as considering the constraints imposed by the topic, the needs of the reader, or the most coherent way to organize the text.” (p. 21)

Why Teach Handwriting?

- Handwriting instruction produces significantly better writing quality and productivity. Students’ sentence-writing skills, the amount they write, and the quality of their writing all improve along with their handwriting.

- Letter writing and fluency are related to both spelling and word reading. Handwriting supports and reinforces the learning of letter names and sound-letter correspondences.

- Teaching handwriting underscores the idea that writing is a communication tool and reminds students that they need to produce text that is legible for other readers.

- As students get older, the quality of their handwriting influences the way their writing is evaluated and graded.

(Graham, 2009-2010; Santangelo & Graham, 2015; Coker & Ritchey, 2015; Reutzel et al., 2017)

Handwriting Instruction

There is significant research spanned over decades demonstrating that directly teaching handwriting enhances legibility and fluency (Graham 2009-2010). Handwriting instruction does not require a significant time investment, and opportunities to practice handwriting can be found throughout the school day. Based on research, Graham suggests that in kindergarten through grade 3, handwriting should be taught in short sessions several times a week or even daily, with 50 to 100 minutes a week devoted to its mastery.

There are three main aspects of handwriting instruction: pencil grasp, letter formation using writing strokes, and legibility.

Pencil Grip

Students need to be taught the correct way to grip a pencil so they can have optimal control over the pencil point. A tripod grip can support this where the index finger and thumb hold the pencil against the middle finger. Students with a poor pencil grasp may benefit from using tools such as a pencil grip.

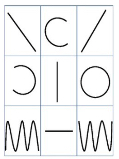

Letter Formation: Teaching Writing Strokes

Printing letters (manuscript) is a developmentally appropriate first step for handwriting instruction in kindergarten through grade 2. Letters can be grouped based on size and alignment. There are short letters (a, c, e, i, m, n, o, r, s, u, v, w, x, z), tall letters (b, d, f, h, k, l, t), and letters that extend below the line (g, j, p, q, y). Students should be taught a consistent way to form a given letter every time they write it, and then practice forming that letter many times to develop automatic and fluent handwriting skills.

Letters are produced by a series of strokes that form curved and straight lines in different directions that are linked together. A stroke-based approach builds motor memory for the different combinations of strokes that are used to write letters. While some letters (e.g., f, t) require students to lift the pencil from the paper to make a second stroke, it is best to teach letter formation using a continuous stroke. Continuous stroke printing improves legibility, reduces letter reversals and directionality confusion, and increases the speed and flow of printing. Here are two examples:

- b: Start at the top with a vertical stroke, then make the loop to the right without lifting the pencil rather than form the line and the loop in separate strokes.

- m: Start at the top and draw the line down, then trace back up to start the first curve, then trace back up the first curve to make the second curve.

Students benefit from explicit instruction in how to form letters. This includes the teacher modeling by verbally explaining how to form a letter. Rhymes or songs can be used to help students remember the steps to form letters.

Students also benefit from lots of practice writing letters. Brief practice sessions are more effective than longer, periodic sessions. In the early grades, daily practice of 5-10 minutes per day is recommended. Students may need multiple opportunities (at least 5-10 times) to practice a letter using a variety of different practice formats such as copying and tracing on paper, or by tracing letters in something that gives tactile reinforcement (e.g., sand, rice, shaving cream). (Coker & Ritchey, 2015)

Letter Formation During Instruction for Letter Naming and Sound-Letter Correspondence

Research has demonstrated a correlation between letter-naming and letter-writing fluency (Reutzel et. al., 2017). Handwriting should be integrated with beginning phonics instruction. As students learn to write the features of letters, they also learn to recognize them more fluently. Students should be taught how to form the uppercase and lowercase of a letter as they learn each letter. Practice with letter formation should be combined with learning sound-letter correspondences. As students write a letter, have them name it and say its sound.

Instructional Suggestions:

- Encourage students to begin all uppercase letters from the top and lowercase letters from the middle or top.

- Practice letters in groups that have similar shapes so students have practice reinforcing the same motor pattern. Examples:

- straight-line letters: i, l, t

- letters that start with a small c shape: a, c, d, g, o, q, s

- letters that start with a straight line down and then come back up and over to form a bump: b, h, m, n, p, r

- diagonal letters (more difficult to form): k, v, w, x, y, z

- Spiral back each day to review previously taught letters.

- At first, focus on having students learn the correct motor movement to form a word. Focus attention on legibility once there is motor memory.

- Always provide visual guidance for what a letter should look like and use visual aids such as arrow cues for stroke direction and dotted letters for tracing.

Legibility

The following elements affect legibility: letter formation, letter spacing, letter alignment, letter size, word spacing. Teachers should provide specific feedback to students about how they can improve the legibility of their writing. To support letter formation and size, provide specially lined paper. For each line of print, there is a horizontal, dotted line in the middle. Short letters are written below the dotted line and above the bottom line. Tall letters are written between the top and bottom lines. The letters g, j, p, q, y extend below the bottom line.

For problems with word spacing, students can be taught to use a space between words by placing a popsicle stick or a finger after one word before starting another.

Additional Resources:

- Article: “Want to Improve Children’s Handwriting? Don’t Neglect Their Handwriting” by Steve Graham.

- Article: “Strengthening the Mind’s Eye: The Case for Continued Handwriting Instruction in the 21st Century” by Virginia Berninger

- Video: “Neuroscientists Say It’s Too Soon to Abandon Handwriting” (offered by Edutopia)

References:

- Coker, D. J., & Ritchey, K. D. (2015). Teaching beginning writers. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Graham, S. (2009-2010). Want to improve children’s writing? Don’t neglect their handwriting. American Educator, Winter 2009-2010.

- Reutzel, P., Mohr, K.A.J., & Jones, C. D. (2017). Exploring the relationship between letter recognition and handwriting in early literacy development. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy. 19 (3) 349-374.

- Santangelo, T. & Graham, S. (2015). A comprehensive meta-analysis of handwriting instruciton. Educational Psychology Review 28 (2).

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

I am a high school English teacher. Many of my students did not learn cursive in grade school. Their handwriting is terrible. After Covid, we are trying to stay off the computers as much as possible.

What do you recommend to improve their hand writing at the age of 14- 15?

Rough drafts on graphic organizer a are a challenge to read.

Please advise.

This is not an easy question to answer! There are students that show that cursive handwriting (where students use continuous strokes from letter to letter) is easier for students who struggle, especially those with dysgraphia. The question, however, is about the time it takes to teach this to older students…. i.e., would this time be better spent developing more automatic keyboarding skills. Given how much typing is used on widely used devices, and the advantages of editing features such as cutting and pasting, if there is limited time it might be better spent on developing keyboarding and word editing skills. Another related note: for students who significant difficulty handwriting and keyboarding, text to speech software can be a real help.

Good advice as always, Joan. Thanks for sharing your expertise!

I agree, this advice is really helpful!

What a great article! Thank you! I have found this program, Printing Like a Pro, seems to match your criteria of a good program and I use it every year. It is free, OT developed and within the page gradually releases the students from a constrained outline to independently forming the letters… http://www.childdevelopment.ca/SchoolAgeTherapy/SchoolAgeTherapyClassResources.aspx?fbclid=IwAR3W7o9Z4-6VyEKD679rTwfZcvJT46Kqa53E425vdatNXngcq1di27qK4qs

Thanks for this, Joan! I diligently work to teach handwriting/spelling as a significant contributor to reading. But, I don’t have great materials. Currently, I use Zaner-Bloser to support handwriting for my K-2, but I wish the practice words were decodable at the appropriate level. Do you have any advice about handwriting resources that give kids words to practice that are more in line with SOR? Also, I teach refugees, so many of my older students, including teens and adults, are learning manuscript printing and English reading for the first time. Any ideas on resources that are not overly juvenile? Thanks!

I adore “The Writing Rope” and just finished your article on handwriting. Do you have any suggestions on a program that is science-based/evidence-based to teach handwriting? Thank you!

This is the most thorough article I have read on handwriting instruction. Thank you. Katoba from Lusaka, Zambia.

Great insights on teaching handwriting! I especially appreciated the emphasis on building fine motor skills and creating a positive learning environment. These strategies seem essential for fostering a love for writing in children. Looking forward to applying these techniques!

I think it really good work be blessed

I loved this post! Teaching handwriting is such an important skill that often gets overlooked in today’s digital age. It’s refreshing to see a focus on the fundamentals—especially how crucial it is for children to develop good handwriting habits early on. I particularly appreciated the tips on breaking down the process into manageable steps, and how incorporating fun activities can make learning more engaging. Handwriting is not just about forming letters, but also about building fine motor skills, coordination, and confidence. Thanks for sharing these great strategies!