Text Driven Comprehension and Close Reading Instruction

Basic comprehension strategy instruction, close reading instruction, and text-driven instruction are closely related. Comprehension strategy instruction provides the foundational, basic comprehension skills that students need to get “under their belt” in order to apply the more complex, critical thinking skills required to closely read challenging text. Basic comprehension strategy instruction should be text-driven — i.e., taught and practiced using content-related text. Teachers will not be effective if strategies (such as main idea and summarizing skills) are taught and practiced in isolation. Likewise, close reading skills need to be text-driven – i.e., using challenging content-related text.

I decided to write about this topic because several teachers have asked me to explain the difference between close reading instruction and comprehension strategy instruction. There are two related resources that I would like to share as part of this blog entry:

- Tim Shanahan’s January 10, 2016 blog post “Close Reading and Reading of Complex Text Are Not The Same Thing”

- Louisa Moats’ archived webinar “Text-Driven Comprehension Instruction”

Moats’ webinar begins by emphasizing that comprehension strategy instruction should be embedded in real text, citing Daniel Willingham’s 2006 article The Usefulness of Brief Instruction in Reading Comprehension Strategies in which he makes the case for limiting explicit instruction of isolated strategies that are practiced out of context. This is also the basic tenet of The Key Comprehension Routine professional development – train teachers to provide instruction for teaching main idea skills, using graphic organizers, taking notes, writing summaries, and generating questions based on content-related sample text, both narrative and expository.

She goes on to provide some excellent, detailed suggestions for preparing a piece of challenging text for a close reading lesson in which the teacher identifies where students might miss something because of complex language that is used. She points out that students who comprehend poorly almost always have weaknesses in their knowledge of language and ability to comprehend abstract language, including figurative language, complex sentences, and language that is difficult to understand because of tone or the way it is stated. In the webinar, Moats takes participants through a detailed analysis of a sample piece of challenging text (about the Greek myth Perseus and the Gorgon’s Head) and shows specific places in the text where teachers might provide explicit instruction, explanation, and modeling for how to unpack that text. Educators who have taken our Keys to Close Reading professional development will recognize similar suggestions for planning a close reading lesson.

Shanahan’s blog piece makes a distinction between his description of close reading (“an approach to text interpretation that focuses heavily not just on what a text says, but on how it communicates that message”) and reading complex text (“text that includes rhetorical features, literary devices, layers of meaning, graphic elements, symbolism, structural elements, cultural references, and allusions”). He also points out that text complexity includes linguistic elements that might make one text more difficult than another (i.e., the kinds of complex language that Moats addresses – sentence complexity, cohesion, text organization, and tone). Shanahan points out that if teachers are going to teach students to closely read to interpret what an author is saying (what he calls close reading), they also need to teach reading comprehension skills to figure out what the text’s sentences are saying (what he calls reading complex text). In this sense, he sees the two as different.

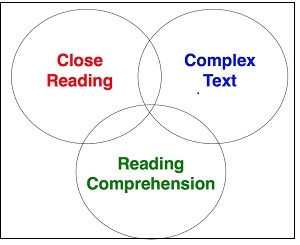

The fine points and distinctions that Moats and Shanahan make between complex text, close reading, and text-driven reading comprehension instruction are useful and fascinating for literacy educators. However, general education content teachers are typically looking for a more basic explanation of how they are similar and different. Here’s my attempt at a short answer:

- Text-driven reading instruction teaches reading comprehension using content-based text. The text may range from mildly challenging (e.g., grade-level textbooks) to significantly challenging (e.g., text that is linguistically/language complex as well as difficult to interpret the author’s message).

- Close reading is something that a student does – a set of critical thinking and analysis skills that are used to unpack linguistically complex text. A close reading lesson is something a teacher plans to explicitly teach and model how to closely read. Text used for a close reading lesson should be significantly challenging.

- Students need to learn and practice basic comprehension skills and strategies using mildly challenging content-related text before they can be expected to learn and apply the more complex critical thinking required for close reading.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

Joan Sedita is the founder of Keys to Literacy and author of the Keys to Literacy professional development programs. She is an experienced educator, nationally recognized speaker and teacher trainer. She has worked for over 35 years in the literacy education field and has presented to thousands of teachers and related professionals at schools, colleges, clinics, and professional conferences.

I have been looking through many of the articles on the Keys to Literacy site and love that all of this is at my fingertips so thank you. The information is thorough, up-to-date, and realistic for use in a classroom. I am, however, disappointed that many of the links don’t work.

Teachers must prepare students by gradually increasing text complexity and explicitly teaching comprehension and vocabulary skills before expecting independent close reading.